History Repeats: The Serpent on the Rock

“History Repeats. The first time as a tragedy, the second time as a farce.”

– Karl Marx(1)

There are amusing parallels between the rise and fall of the real estate private partnership market in the 1980s, the pre financial crisis tenant in common(TIC) syndication market, and the post financial crisis non-traded REIT market driven by Nick Schorsch and his AR Global empire.

Each episode involved high fee investment products designed to fulfill investor desires for yield, tax efficiency and perceived stability, while creating disproportionate benefits for intermediaries. Each episode ended badly. And the cycle repeats, again and again.

First of all, the charts tell parallel stories:

Real Estate Limited Partnerships 1970-1991

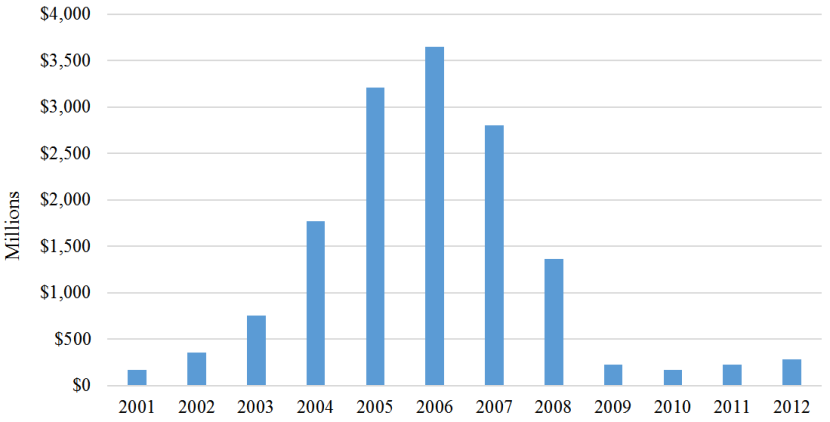

TIC Equity raised 2001-2012:

Source: Securities Litigation and Consulting Group

Non-traded REIT Equity Raise 2000-2016:

Source: Stanger Report, author’s calculations based on SEC filings.

Note that the 2015-2016 dropoff would be much sharper if you excluded Blackstone’s REIT, which entered the wirehouse channel in late 2016, and accounted for 50% of total annual NT REIT sales within a few months. Sales to the independent broker dealer(IBD) channel, which Blackstone largely bypasses, were completely decimated, and the dropoff has accelerated in 2017. (2)

May Day

High fee products are sold, not bought. The commissions on illiquid real estate products have always been higher than other investments available to retail investors.

In Serpent on the Rock Eichenwald traces the original real estate partnership craze back to the May 1, 1975 abandonment of fixed commissions on sale of stocks and bonds. Yes it is viciously ironic that commissions were fixed before 1975. The financial services industry was apparently afraid of capitalist competition and all the wonderful creative destruction it brings. Once they lost large commissions on simple security trades, they went looking through more complex higher fee product.

After May Day:

No longer could brokerage firms subsidize their bloated through fat commissions on securities trades. Firms unable to adjust collapsed by the dozens. The industry had to either dramatically cut back expenses or find new products with higher commissions that could be pumped through the sales force. Suddenly tax shelters, which sold for higher commissions than stocks and bonds didn’t look so unappealing.

The impact of May Day has continued to drive down commissions decades later. This makes sense. After all, transactional costs should approach zero over the long run, because with computers the marginal cost of doing a trade in all but the most illiquid complex markets is effectively zero. Significant scale and technological investment is necessary to run a brokerage business focused on liquid markets.

Consequently, the current IBD ecosystem is highly dependent on non-traded REITs and other high fee direct private placement programs. This is complicated by the fact that IBDs payout a high proportion of commissions to the financial advisers(like 90% in many cases). Many financial advisers built their business on 1031 exchanges, non-traded REITs or other private placements. TICs typically charged 20-30% commissions. Commissions eat up a large portion of offering proceeds for non-traded REITs. Additionally, non-traded REIT sponsors pay out a due diligence kickback to broker dealer home offices. Many smaller IBDs depend on these kickbacks for survival.

Of course, the commissions were much more egregious the first time around. Old timers fondly remember 20%+ loads on product. up front sales loads have now declined to high single digits and low double digits. Inland has driven down commissions on 1031 exchange product. Plus state securities regulators put out NASAA guidelines to limit loads on registered products. Nonetheless in an age where interactive Brokers charges $1 per side on a trade regardless of size, and few modern brokerages charge more than $7 per trade, even high single digit sales loads on non-traded retail product are absurd.

In Backstage Wall Street Josh Brown outlines his “Iron law of product compensation”:

The higher the commission or selling concession a broker is paid to sell a product, the worse that product will be for his or her clients.

This was the thread that connects the 1980s private partnership craze, with the pre financial crisis TIC explosion and the post financial crisis non-traded REIT market.

Yield Pig Exploitation and the Illusion of Safety

Just like private partnerships in the 1970s and 1980s, brokers sold TICs and Non-traded REITs to unsophisticated yield hungry retirees as safe, stable investments.

Here is one description of the private partnership market:

Many of the public offerings were promoted as a way for the small investor to participate in real estate, widely believed to be an inflation hedge, offering greater return and moderate risk as compared to stocks. The ability for an individual of modest net worth or income to invest in securitized real estate was viewed as a real benefit of public syndications.

The limited partners were sold their investments on the assumption that real estate was a safe, growing investment. Often these investors were unsophisticated in investment matters, and were more often swayed by aggressive brokerage salesmanship. The importance of liquidity became apparent to the investors only after substantial investment had already occurred. Liquidity was never promised for limited partnership securities and the partnership structure itself was designed to constrain liquidity.

In Serpent on the Rock Eichenwald meticulously tracked the juxtaposition between sales materials promising safety and the ultimate collapse in values.Non-traded REITs and TICs are also sold as safe investments that do not have the volatility of the stock market. Of course the stability is an illusion, and investors are still highly dependent on the real estate performance.

Due diligence

Eichenwald describes due diligence at Prudentialduring the peak of the private partnership craze:

The due diligence team was not just overwhelmed from the number new deals they had to approve- they also had to keep tabs on the old deals that had already been sold. Darr had negotiated for Bache to be paid a monitoring fee from some tax shelters it sold in exchange for reviewing their financial performance. Supposedly, this was designed to make sure that the general partners managing the deals did things right and took care of their investors. It was a key selling point for Bache brokers: In sales pitches, they painted a picture of top Bache financiers in green eyeshades peering over the shoulders of the General partners, watching everything that was done, The image of financial professionals crunching numbers late into the night to make sure investors were protected was a persuasive marketing tool.

But asset monitoring paid only a small fraction of the fees that Bache received from selling new deals. So the job of keeping an eye on the performance of old shelters quickly became viewed as simply a headache. It was an obligation that slowed down the whole process of churning out deals., without enough juice from fees to make up for the effort. The monitoring assignment became a hot potato, passed from executive to subordinates, and from then on down the line.

Many similar scenes in the book are shockingly familiar to anyone who has worked in the alternative investments space.

In subsequent years, third party due diligence firms serving broker dealers helped drive improvements in deal quality, but there are still many serious gaps. Since IBDs depend on the revenue from commissions and due diligence kickbacks, they are under pressure to find product to approve. This bias leads to cognitive dissonance. As non fiduciary middlemen, they often sell things that they wouldn’t invest in themselves, especially with a full sales load.

In the wake of the bankruptcy of TIC Sponsor DBSI, and the collapse of several tax driven energy deals, Reuters investigated due diligence in the independent broker dealer space. It highlighted a too cozy relationship between sponsors and third party due diligence firms.

Perhaps of even greater concern is the disconnect between due diligence process and the needs of end investors.

Potentially alarming findings are often obscured in multiple pages of recondite language, with no definitive conclusions. “They’re these long-winded things that bury things that might be important inside boilerplate disclosures,” said Jennifer Johnson, a professor at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon, who has written extensively about the private-placement business.

Due diligence firms say their reports aren’t designed to be read or understood by investors. Rather, they are meant to help brokers decide whether to recommend private placements to their customers.

Same Same, But Different

Although the distorted incentives,exploitation of unsophisticated yield pigs,were almost identical in each of the three historical examples in this post, there are several key differences. Broker dealers primarily sold private partnerships in the 1980s as a way of reducing taxes. An investor can use a TIC structure as part of a 1031 exchange to delay taxes when selling a property. REITS are a unique IRS creation but the reason for investing in a REIT is mainly income(Excluding situations where someone exchanges via an UPREIT transaction)

The private partnership market collapsed because the tax reform act of 1986 destroyed their entire structure, and basically collapsed the national real estate market. (see: this FDIC report )

The TIC market collapsed when the financial crisis hit the entire real estate market, exposing the problematic underwriting of the TIC Sponsors. However, regulatory issues weren’t the main driver of the collapse. Like the private partnership craze in the 1980s, the modern Non-traded REIT market also collapsed due to regulatory change although the . Finra 15-02, which increased the transparency on client statements, made it harder for advisors to get away with charging the massive sales loads. The fiduciary standard required broker-dealers to act in the best interest of clients, also led many broker-dealers to suspend or slow down the sales of high commission products.

The farce of AR Global’s collapse

Although private partnerships and TIC sponsors generally overpaid for properties they purchased, the collapse of their structures happened during a time of across the board real estate declines in the US

In contrast, investors in post financial crisis vintage non-traded REITs have suffered, in spite of a buoyant real estate market. ARC Hospitality(Now Hospitality Investors Trust) offered shares at $25.00 a share from 2013-2015, and a client statement never would have shown a value below $22.00 until this summer. It revalued at $13.20. A PE fund recently offered $5.53 for the shares. Likewise ARC Healthcare Trust III sold shares $25.00, and recently marked its value down to $17.64, and is now subject to an affiliated transaction with no liquidity event in site.

Private partnerships and TICs were tragedies, AR Global was a farce.

To be continued….

(1) This is from The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napolean.

The full translated quote is :Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

(2) Wirehouses generally did not sell non-traded REITs until Blackstone entered the market in 2016 Anyone who carefully read The Serpent on the Rock will note how incredibly ironic it is that wirehouses have started to sell non-traded real estate securities again. More on his in a future post.

2 comments