Test counter-intuitive things because no one else ever does

Alchemy one of a small set of books that helped fill out important gaps in my understanding of how the world works. Its essential reading for people who think they are logical, and valuable for everyone else. I’ve organized my (copious) notes and highlights around key themes below. But seriously you should just get the book.

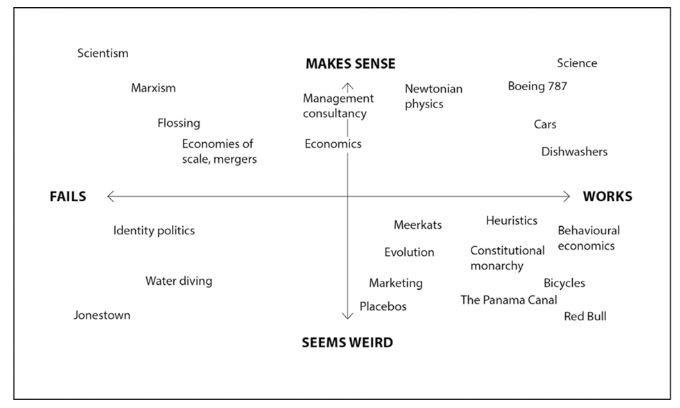

- Not everything that makes sense works, and not everything that works makes sense.

- Test counterintuitive things and ask dumb questions .

- Never denigrate something as irrational until you have considered what purpose it really serves.

- Try to understand the real reason for things(not the surface reason)

- Cooperation has major evolutionary value, but most deductive logical thinking ignores it.

- If you optimise incentive systems(or anything else) in one direction, you may be creating a weakness somewhere else.

- People are way too confident in traditional technocratic approaches and big data solutions relative to how well they actually work

- Hacking personal improvement: Many important features of the human brain are not under our direct control but are instead the product of instinctive and automatic emotions.

- Embrace uncertainty.

Not everything that makes sense works, and not everything that works makes sense.

We used to have a shortage of conventional deductive logic. Now we have too much. Conventional deductive logic is often a good thing. However we have venerated this manner of thinking so much that we have become blind to the situations in which it doesn’t work. Complex and evolved systems are not consciously designed, and often second order consequences that aren’t readily apparent are more important than what can be analyzed on the surface. Evolution doesn’t care if things make sense- it only cares if things work. Therefore, trial and error usually works better than reasoning everything out before acting.

Often when a phenomenon or group behavior doesn’t seem logical/rational, it is because the observer has an incomplete model of reality.

Not everything that makes sense works, and not everything that works makes sense. The top-right section of this graph is populated with the very real and significant advances made in pure science, where achievements can be made by improving on human perception and psychology. In the other quadrants, ‘wonky’ human perception and emotionality are integral to any workable solution. The bicycle may seem a strange inclusion here: however, although humans can learn how to ride bicycles quite easily, physicists still cannot fully understand how bicycles work. Seriously. The bicycle evolved by trial and error more than by intentional design.

There are two separate forms of scientific enquiry – the discovery of what works and the explanation and understanding of why it works. These are two entirely different things, and can happen in either order. Scientific progress is not a one-way street. Aspirin, for instance, was known to work as an analgesic for decades before anyone knew how it worked. It was a discovery made by experience and only much later was it explained. If science did not allow for such lucky accidents,* its record would be much poorer – imagine if we forbade the use of penicillin, because its discovery was not predicted in advance? Yet policy and business decisions are overwhelmingly based on a ‘reason first, discovery later’ methodology, which seems wasteful in the extreme. Remember the bicycle. Evolution, too, is a haphazard process that discovers what can survive in a world where some things are predictable but others aren’t. It works because each gene reaps the rewards and costs from its lucky or unlucky mistakes, but it doesn’t care a damn about reasons. It isn’t necessary for anything to make sense: if it works it survives and proliferates; if it doesn’t, it diminishes and dies. It doesn’t need to know why it works – it just needs to work.

Perhaps a plausible ‘why’ should not be a pre-requisite in deciding a ‘what’, and the things we try should not be confined to those things whose future success we can most easily explain in retrospect. The record of science in some ways casts doubt on a scientific approach to problem solving.

Like thinking fast and slow, Alchemy makes an intellectual reader see the value of humility:

Once you accept that there may be a value or purpose to things that are hard to justify, you will naturally come to another conclusion: that it is perfectly possible to be both rational and wrong. Logical ideas often fail because logic demands universally applicable laws but humans, unlike atoms, are not consistent enough in their behaviour for such laws to hold very broadly.

It’s true that logic is usually the best way to succeed in an argument, but if you want to succeed in life it is not necessarily all that useful; entrepreneurs are disproportionately valuable precisely because they are not confined to doing only those things that make sense to a committee

… if we allow the world to be run by logical people, we will only discover logical things. But in real life, most things aren’t logical – they are psycho-logical. There are often two reasons behind people’s behaviour: the ostensibly logical reason, and the real reason

Test counterintuitive things, ask dumb questions

Alchemy provides the blueprint for a type of inversion one can do in approaching problems.

Test counterintuitive things, because no one else ever does.

Here’s a simple (if expensive) lifestyle hack. If you would like everything in your kitchen to be dishwasher-proof, simply treat everything in your kitchen as though it was; after a year or so, anything that isn’t dishwasher-proof will have been either destroyed or rendered unusable. Bingo – everything you have left will now be dishwasher-proof! Think of it as a kind of kitchen-utensil Darwinism. Similarly, if you expose every one of the world’s problems to ostensibly logical solutions, those that can easily be solved by logic will rapidly disappear, and all that will be left are the ones that are logic-proof – those where, for whatever reason, the logical answer does not work.

Most political, business, foreign policy and, I strongly suspect, marital problems seem to be of this type.

Similarly, if you expose every one of the world’s problems to ostensibly logical solutions, those that can easily be solved by logic will rapidly disappear, and all that will be left are the ones that are logic-proof – those where, for whatever reason, the logical answer does not work. Most political, business, foreign policy and, I strongly suspect, marital problems seem to be of this type.

The mental model at work here is like a broader application of the case in World War II , where Navy analysts had to figure out how to build stronger planes not by thinking about the missing bulletholes.

Closely related is how great insight comes from asking dumb questions. Leaders must allow and encourage their team to ask dumb questions:

This freedom is much more valuable than we realise, because to reach intelligent answers, you often need to ask really dumb questions.

Never denigrate something as irrational until you have considered what purpose it really serves.

There are a lot of social psychology lessons in Alchemy Many of them are more fun(and easier to process) examples of the phenomonen revealed through evolutionary case studies in Secrets of Our Success.

There is an important lesson in evaluating human behaviour: never denigrate a behaviour as irrational until you have considered what purpose it really serves

Try to understand the real reason for things(not the surface reason)

Sometimes behavior that seems illogical has a hidden evolutionary value. People make mistakes when they judge others by surface actions, without considering things working below the surface.

there is an ostensible, rational, self-declared reason why we do things, and there is also a cryptic or hidden purpose. Learning how to disentangle the literal from the lateral meaning is essential to solving cryptic crosswords, and it is also essential to understanding human behaviour.

….Sometimes human behaviour that seems nonsensical is really non-sensical – it only appears nonsensical because we are judging people’s motivations, aims and intentions the wrong way. And sometimes behaviour is non-sensical because evolution is just smarter than we are. Evolution is like a brilliant uneducated craftsman: what it lacks in intellect it makes up for in experience.

….One problem (of many) with Soviet-style command economies is that they can only work if people know what they want and need, and can define and express their wants adequately. But this is impossible, because not only do people not know what they want, they don’t even know why they like the things they buy. The only way you can discover what people really want (their ‘revealed preferences’, in economic parlance) is through seeing what they actually pay for under a variety of different conditions, in a variety of contexts. This requires trial and error – which requires competitive markets and marketing.

There are no universal laws of human behaviour:

Our very perception of the world is affected by context, which is why the rational attempt to contrive universal, context-free laws for human behaviour may be largely doomed.

Cooperation has major evolutionary value, but most deductive logical thinking ignores it

Humans are a social species. This is not exactly a big insight, yet much of standard applied psychology and economics actually ignores this in practice. Indeed many ostensibly logical people ignore this in attempting to understand the world. This is made worse by the contrived nature of a lot of academic research.

Robert Zion, the social psychologist, once described cognitive psychology as ‘social psychology with all the interesting variables set to zero’. The point he was making is that humans are a deeply social species (which may mean that research into human behaviour or choices in artificial experiments where there is no social context isn’t really all that useful).

Humans are willing to forgoe short term expediency in order to cooperate and sacrifice for other people.

This is not irrationality – it is second-order social intelligence applied to an uncertain world.

There is an important biological reason:

Unlike short-term expediency, long-term self-interest, as the evolutionary biologist Robert Trivers has shown, often leads to behaviours that are indistinguishable from mutually beneficial cooperation. The reason the large fish does not eat its cleaner….

If fish (and even some symbiotic plants) have evolved to spot this sort of distinction, it seems perfectly plausible that humans instinctively can do the same, and prefer to do business with brands with whom they have longer-term relationships. This theory,

As a result, like any social species, we need to engage in ostensibly ‘nonsensical’ behaviour if we wish to reliably convey meaning to other members of our species.

One of the most important ideas in this book is that it is only by deviating from a narrow, short-term self-interest that we can generate anything more than cheap talk. It is therefore impossible to generate trust, affection, respect, reputation, status, loyalty, generosity or sexual opportunity by simply pursuing the dictates

There is a parallel in the behaviour of bees, which do not make the most of the system they have evolved to collect nectar and pollen. Although they have an efficient way of communicating about the direction of reliable food sources, the waggle dance, a significant proportion of the hive seems to ignore it altogether and journeys off at random. In the short term, the hive would be better off if all bees slavishly followed the waggle dance, and for a time this random behaviour baffled scientists, who wondered why 20 million years of bee evolution had not enforced a greater level of behavioural compliance. However, what they discovered was fascinating: without these rogue bees, the hive would get stuck in what complexity theorists call ‘a local maximum’; they would be so efficient at collecting food from known sources that, once these existing sources of food dried up, they wouldn’t know where to go next and the hive would starve to death. So the rogue bees are, in a sense, the hive’s research and development function, and their inefficiency pays off handsomely when they discover a fresh source of food. It is precisely because they do not concentrate exclusively on short-term efficiency that bees have survived so many million years.

If you optimise incentive systems(or anything else) in one direction, you may be creating a weakness somewhere else.

Incentives, incentives incentives.

In institutional settings, we need to be alert to the wide divergence between what is good for the company and what is good for the individual. Ironically, the kind of incentives we put in place to encourage people to perform may lead to them to be unwilling to take any risks that have a potential personal downside – even when this would be the best approach for the company overall. For example, preferring a definite 5 per cent gain in sales to a 50 per cent chance of a 20 per cent gain.

If you optimise something in one direction, you may be creating a weakness somewhere else.

In any complex system, an overemphasis on the importance of some metrics will lead to weaknesses developing in other overlooked ones. I prefer Simon’s second type of satisficing; it’s surely better to find satisfactory solutions for a realistic world, than perfect solutions for an unrealistic one. It is all too easy,

See Also: Goodhart’s Law and the Fall of Nick Schorsch , Department of Unintended Consequences, The Value of Improvisation and Informal Processes

People are way too confident in traditional technocratic approaches and big data solutions relative to how well they actually work

We don’t need to throw out economic models- but we need to spend time considering what htey ignore.

By using a simple economic model with a narrow view of human motivation, the neo-liberal project has become a threat to the human imagination.

…The alchemy of this book’s title is the science of knowing what economists are wrong about. The trick to being an alchemist lies not in understanding universal laws, but in spotting the many instances where those laws do not apply. It lies not in narrow logic, but in the equally important skill of knowing when and how to abandon it. This is why alchemy is more valuable today than ever.

…The technocratic mind models the economy as though it were a machine: if the machine is left idle for a greater amount of time, then it must be less valuable. But the economy is not a machine – it is a highly complex system. Machines don’t allow for magic, but complex systems do. …

…We should absolutely consider what economic models might reveal. However, it’s clear to me that we need to acknowledge that such models can be hopelessly creatively limiting. To put it another way, the problem with logic is that it kills off magic. Or, as Niels Bohr* apparently once told Einstein, ‘You are not thinking; you are merely being logical.’ A strictly logical approach to problem-solving gives the reassuring impression that you are solving a problem, even when no such process is possible; consequently the only potential solutions considered are those which have been reached through ‘approved’ conventional reasoning – often at the expense of better (and cheaper) solutions…

The advent of big data doesn’t change this:

We should also remember that all big data comes from the same place: the past. Yet a single change in context can change human behaviour significantly. For instance, all the behavioural data in 1993 would have predicted a great future for the fax machine.

Tangentially related, Alchemy connects economics with psychology and evolutionary biology in a better way than just about anything else I’ve read(some other examples see: Ecological Consequences of Hedge Fund Extinction)

Because they offer competing choices, consumer markets provide a guide to our unconscious in a way that theories don’t. For this reason, I have called consumer capitalism ‘the Galapagos Islands for understanding human motivation’; like the beaks of finches, the anomalies are small-but-revealing.

Hacking personal improvement: Many important features of the human brain are not under our direct control but are instead the product of instinctive and automatic emotions.

Alchemy has many insights for how one can approach personal improvement, and “hacking oneself.” Many important features of the human brain are not under our direct control but are instead the product of instinctive and automatic emotions:

There is a good evolutionary reason why we are imbued with these strong, involuntary feelings: feelings can be inherited, whereas reasons have to be taught, which means that evolution can select for emotions much more reliably than for reasons. To ensure your survival, it is much more reliable for evolution to give you an instinctive fear of snakes at birth than relying on each generation to teach its offspring to avoid them. Things like this aren’t in our software – they are in our hardware.

Useful to have a machine metaphor. I think of it like a computer. He uses a car:

…The truth is that you can control the gearbox of an automatic car, but you just have to do it obliquely. The same applies to human free will: we can control our actions and emotions to some extent, but we cannot do so directly, so we have to learn to do it indirectly – by foot rather than by hand.

Closely related, he had some insights into the placebo effect:

The placebo effect, like many other forms of alchemy, is an attempt to influence the mind or body’s automatic processes. Our unconscious, specifically our ‘adaptive unconscious’ as psychologist Timothy Wilson calls it in Strangers to Ourselves (2002), does not notice or process information in the same way we do consciously, and does not speak the same language that our consciousness does, but it holds the reins when it comes to much of our behaviour. This means that we often cannot alter subconscious processes through a direct logical act of will – we instead have to tinker with those things we can control to influence those things we can’t or manipulate our environment to create conditions conducive to an emotional state which we cannot will into being.

The actions required to create such conditions may involve a certain degree of what appears to be bullshit – but it is only bullshit when you don’t know what its reason is. It is this oblique hacking of unconscious emotional and physiological mechanisms that often causes suspicion of the placebo effect, and of related forms of alchemy. Essentially we like to imagine we have more free will than we really do, which means we favour direct interventions that preserve our inner delusion of personal autonomy, over oblique interventions that seem less logical.

Embrace uncertainty

Many problems come from seeking out false certainty. Avoiding uncertainty can have social benefits within certain institutions, and it can abodi discomfort. But ultimately certainty is an illusion, and pretending it is reality is a disaster. Embracing uncertainty is a prerequisite to major breakthroughs. See also: Thinking in Bets

The modern education system spends most of its time teaching us how to make decisions under conditions of perfect certainty. However, as soon as we leave school or university, the vast majority of decisions we all have to take are not of that kind at all. Most of the decisions we face have something missing – a vital fact or statistic that is unavailable, or else unknowable at the time we make the decision. The types of intelligence prized by education and by evolution seem to be very different. Moreover, the kind of skill that we tend to prize in many academic settings is precisely the kind that is easiest to automate.

If you want to look like a scientist, it pays to cultivate an air of certainty, but the problem with attachment to certainty is that it causes people completely to misrepresent the nature of the problem being examined, as if it were a simple physics problem rather than a psychological one.

Related Ockham’s Notebook Posts

- Why its Wise to Think in Bets

- The Ecological Consequences of Hedge Fund Extinction

- Empty Spaces on Maps

- Goodharts Law and the Fall of Nick Schorsch

- Department of Unintended Consequences

- The Value of Improvisation and Informal Processes

Other Books/Papers: