Is credit really the smart money?

Conventional wisdom holds that credit markets are “smart institutional money” that sees problems faster than equity markets that are full of less sophisticated retail investors. I question whether that is still empirically true. Retail investors now own large portions of the credit market, including high yield. Credit markets appear to be distorted by a combination of indexation and a reach for yield. Its possible that bonds trading at par can be a false comfort signal for an equity investor looking at a highly leveraged company, because in many recent cases equity markets have been faster to react to bad news.

Retail ownership of credit markets.

However you slice and dice the data, there is clearly a lot more retail money in credit than there was a decade ago. The media mostly reports on noisy weekly or monthly flows, even though there has been a clear long term change.

Bond funds in general have experienced dramatic inflows over the past decade:

Source: ICI Fact Book 2017

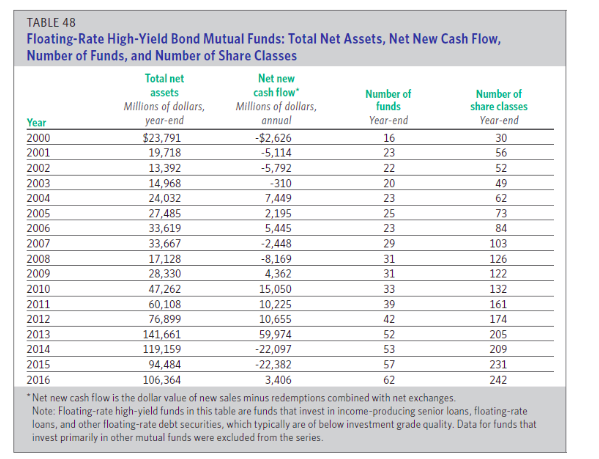

The issues becomes more serious when you look just at the high yield part of the market. Boaz Weinstein of Saba Capital estimated that between ½ or ⅓ of junk bonds are owned by retail investors in the current market. The WSJ cited Lipper data that says mutual fund ownership of high yield bonds/loans is $97 billion today vs $18 billion a decade ago. ICI slices the data differently, and comes up with a much nosier data set for just floating rate unds, indicating large outflows in 2014 and 2015. However it shows net assets in high yield bond funds up 3x compared to 2007, and the total number of funds up over 2x during that time.

Source: ICI Fact Book 2017

Its not just mutual funds either- there are now more closed end type fund structures that market towards retail investors. BDCs experienced a fundraising renaissance through 2014, and are now active in all parts of the high yield credit markets- from large syndicated loans to lower middle market. Closely related, before the last financial crisis, ago there was minimal retail ownership of CLO equity tranches, but now there are a few specialist funds, and a lot of BDCs have big chunks of it as well. Oxford Lane and Eagle Point were sort of pioneers in marketing CLO investments to retail investors but many others have followed. Interval funds are a tiny niche, but over half the funds in registration are focused on credit. It seems just about every asset manager is cooking up a direct lending strategy. The illiquid parts of the credit market are harder to quantify, but there has been a clear uptick in retail investor exposure since before the financial crisis. The marginal buyer impacting pricing is increasingly likely to be a retail investor rather than an institution.

Retail investors to exhibit more extreme herding behavior. According to Ellington Management Group:

This feedback loop between asset returns and asset flows has magnified the growth of the high yield bubble.

Capital Distortions

Its pretty easy to make a loan, its much harder to get paid back.

-Jeffrey Aronson, Centerbridge Capital

Credit is cyclical, and we are clearly getting into a more dangerous part of the cycle. In frothy markets lending standards deteriorate, and yields are lower than justified by the risk.

Back in 2014, the Office of Comptroller of the Currency started warning that :

Investor demand for high-yield products continued to surge, with more relaxed structures incorporating fewer covenants and lender protections“

Reuters recently reported that Middle Market covenant lite lending reached an all time high in 2017, even higher than it was in 2007. This cyclicality happens whether the investors are retail or instituttional, but the high retail ownership means the overshooting may be severe. Indeed, retail vehicles are among those most likely to be impacted in a downturn, according to the report:

As for types of lenders expected to face the greatest challenges in their loan portfolios this year, 26% of respondents said mezzanine lenders are at the top of the list. Business Development Companies (BDCs) were next in line with 23%, 18% said distressed investors and 14% selected traditional banks. Specialty finance companies and direct lenders were tied at 6.84% each, while bank asset-based lenders and equipment finance companies are ranked least likely to face trouble, at less than 5% each.

“Many BDCs make investments in much smaller companies, which can be more vulnerable to economic contraction. BDCs also have a higher cost of capital relative to regulated banks, which dictates looking to invest in places that justify their cost of capital, which can also translate into added risk,” said Flynn.

There are mutiple othe rexamples of very risky credit trading at prices that don’t reflect risk. HYG, a high yield corporate bond etf tha tinvests in some speculative credit, yields only 5% for example.

From Almost Daily Grant’s yesterday:

This morning, Bloomberg reports that a breakneck rally in triple-C-rated debt (characterized by S&P as: “currently vulnerable to nonpayment and is dependent upon favorable business, financial, and economic conditions for the obligor to meet its financial commitments on the obligation”) has compressed spreads to an average of 579 basis points over Treasurys, tightest in more than three years. In the first week of 2018, triple-C spreads have compressed by 36 basis points. More broadly, the spread between the Bank of America Merrill Lynch High Yield Index and Treasurys has narrowed to 336 basis points, within one basis point of its tightest reading since July of 2007

Horizon Kinetics has pointed outsome of the distortions, as part of its broader analysis of distortions caused by indexation. Essentially bonds that are picked up by index funds tend to have absurdly low yields regardless of credit risk. This problem is further exacerbated by the fact that high yield bond indices are market cap weighted, meaning they buy more of entities as they pile on debt.

According to Horizon Kinetics:

How is it possible that Russian Federation 15‐year bonds trade at the yield of 10‐year IBM bonds? How does a company in the midst of a massive fraud investigation, its senior executives in prison, trade at a yield not much above a diversified index of U.S. high yield bonds? (referring to Petrobras) And, really, how does a nation the size of Vermont, on the brink of collapse, situated where Lebanon is, borrow more cheaply than Wendy’s?

If these yields to maturity are really inadequate compensation for the risk assumed by owning these bonds, do the prices result from some other factor, such as artificial supply‐and‐demand pressures? In EMHY, new money is allocated based on float. In other words, the more debt a nation has issued, the greater the allocation to the bonds of that nation because it has a greater capitalization. That is the mathematical model, and that is entirely logical – to a point.

Somewhere in this country, a robo advisor has just instructed an individual, and an asset allocation committee for a public pension fund has just made an adjustment to their exposures, and both have decided to establish, or add to, their emerging markets high yield segment. EMHY has $228 million in Assets Under Management (“AUM”). If this one pension fund is $10 billion (which wouldn’t even make the list of the largest 300 global pension funds) and wished to allocate merely one‐half of 1% of its portfolio to EMHY, that would be $50 million, or 20% of the ETF. That’s a lot. If the ETF could exercise subjective judgment, perhaps some decisions would be made about how to allocate that $50 million other than according to the existing float‐based weightings and other than immediately. But in this instance, the mathematical model becomes the reality – which is not a good idea. The computer cannot calculate the subjective judgment, however realistic that subjective judgment might be, of the probability of default, nor is there a “valuation” factor, extreme or otherwise, in its program – they simply don’t exist. Accordingly, not only does the computer purchase additional Lebanese bonds in the precisely correct ratio, but if Lebanon issues more bonds in order to stay afloat, the total capitalization of Lebanese bonds increases, and the ETF will assign yet a higher weight to Lebanon and purchase proportionately more…..

False Signals to the Equity Markets

There have been a few recent high profile examples of the global equity market seeming to “get it” faster than the credit markets. Noble Group, a Singapore based trading company had bonds trading around par until the eve of debt restructuring in summer 2017 even as its equity plummeted over a year in advance. A similar phenomenon occurred with Banco Popular in 2017, and I think the junior debt got zero along with the shareholders in the end. Noble Group, a Singapore based trading company had bonds trading above par until the eve of debt restructuring in summer 2017 even as its equity plummeted over 90% from its 2014 level. Is similar phenomenon occurred with Banco Popular in 2017, and I think the junior debt got zero along with the shareholders in the end. In some cases junk bonds fall as much as equity does, so a bond investors gets no added safety from being in a debt instrument rather than equity. Boaz Weinstein of Saba Capital pointed out the example of Chesapeake Energy, where the bonds and stock each dropped closed to 90% around the same time.

In the past it used to be possible to look to the bond market for comfort when analyzing a levered equity, but that no longer seems logical. Apparently some hedge funds have set up interesting counterintuitive pair trades shorting overpriced credit, and buying under priced highly levered equities. Of course in other cases, if both debt and equity are trading at premiums, then the equity may be the first to break.

Lenders be careful out there.

See Also: Minsky and the Junk Bond Era

3 comments