Category: Credit Cycle

Global macro is dead, long live global micro

After Louis Bacon closed Moore Capital this past week, both the FT and the Economist had interesting articles on the future of global macro investing. They struck almost opposite tones, each making good points about the current and future reality. Global macro will return, but likely in an unexpected form.

Stability destabilises a generation of macro hedge fund stars

A league of their own: Do not write off the macro hedge-fund manager just yet

Stability killed the macro star

The glory days of global macro as we know it started when the Bretton Woods system collapsed in 1971, ending fixed exchange rates. Broadly speaking, there were two different groups of investors who entered this environment and profited immensely. The first was people with long/short equity experience in global markets and included George Soros, Jim Rogers, and Michael Steinhardt. The second group included people with a physical commodities and futures background. The Commodities Corporation trading firm trained and/or funded many macro investors including Bruce Kovner, Paul Tudo Jones, Louis Bacon, Michael Marcus, etc.

The dramatic changes in the institutional architecture of international trade and finance created a volatile playground for these investors. Exchanges developed new derivatives instruments for trading newly volatile currencies and increasingly global commodities markets in a high inflation environment. Global trade started to open up dramatically, and global supply chains spidered out in response to changes in policy and technology. Many investors made or lost fortunes betting on big equity moves like the 1987 stock market crash(shortly after Greenspan became head of the Fed), or the breaking of fixed currency regimes such as the sterling crisis of 1992, the Asia crisis of 1997, Russia in 1998, etc. There was also the emerging market debt crisis in the 1980s and the surprise interest rate hike in 1994.

After the 2009 global financial crisis, interest rates and inflation have been abnormally low. The euro crisis notwithstanding, markets have lacked volatility. With no volatility its hard for the traditional global macro style to work. Moore and his proteges have all closed down recently. The decline of the legacy macro investors is just one part of the broader decline of active management. Its been a long torturous capitulation.

Yet stability leads to instability. Long periods of calm tend to be followed by extreme volatility.

The future is global micro

Is there any future for global macro? That depends on what your definition of “global macro is” Making bold systemic predictions about surface level data is unlikely to lead to profits. Yet global macro’s main benefit is its flexibility to take long or short positions in any asset class anywhere in the world. Although trades in large liquid markets get the most attention, the analytical techniques of global macro can also uncover insights leading to lucrative opportunities less liquid frontier, emerging, and alternative markets.

The future of global macro will involving finding bottom up industry and company specific insights that fit with top down shifts: global micro. Steven Drobny mentioned this evolution in Inside the House of Money . Indeed most quantitative techniques of the original macro greats are commoditized. Analysts need to look beyond headline numbers numbers for less obvious global micro trends and second order impacts on tradeable assets.

Capital flows and valuations have a funny historical tendency to overshoot in both directions. Many investors build up leveraged positions based on stale fundamental inputs, and when they wake up to a new narrative taking over the market, they must rush to a crowded exit. What will be the next gestalt shift in which a new narrative takes over markets?

The next gestalt shifts

Don’t try to play the game better, try to figure out when the game has changed

Over coached football players do not respond well when a game takes an unexpected turn. Investors schooled in calmer markets may similarly struggle with renewed volatility.

Many of the classic macro bets(and blowups) involved major breaks in fixed currency regimes. Sometimes the big trade(or blowup) involved direct currency exposure. Other times it involved investments impacted by second order effects. Its possible that the big macro trades of the future will be more subtle, and play out over many years away from headlines before becoming obvious.

For the past few decades, global trade was getting generally more open. That is starting to reverse. The WTO dispute settlement mechanism will completely shut down next month because the Trump administration is blocking new appointments to the appellate body. Trump’s attitude is just an extreme manifestation of a global trend towards populism and trade conflict. At best, there will be a spaghetti bowl of bilateral agreements, instead of a large open multilateral trading system. Companies will need to dedicate more resources to supply chain strategy.

At the same time, emerging markets are starting to trade more with each other than with the developed world. Africa might become the world’s largest free trade area. China is attempting to facilitate more commodities trading without using the dollar. As China develops its own bond markets, it will invest less in US dollar based debt markets. As the world shifts to cleaner energy, oil producers will have fewer dollars to recycle into US capital markets. The relative importance of the US dollar and of major US companies is likely to decline.

Often policy changes have second order impacts on individual businesses because they alter competitive forces in their industries. Indeed its difficult to find an example of businesses that are completely immune to change in international trade policy.

Reality and narratives change at different paces. Narrative changes alter capital flows ultimately impacting valuations.

Here are some other speculations on what shocks or regime shifts might occur:

- I don’t have a strong view on inflation, but do find it concerning how few S&P 500 companies will do well if we encounter high inflation. Its commonly accepted wisdom that low inflation will continue. Yet most analysts are only considered demand driven inflation, and ignoring possible supply side shocks. There has been little investment in new production capacity for many key over the past decade. Note the conspicuous absence of resource companies in the top holdings of any indices. More insidiously, if certain prominent venture funded startups shifted from growth mode to harvest mode, and suddenly needed to make money, they would be forced to raise prices, impacting consumers directly (See: Cheap Stuff and Cheap Capital) . Alternatively, if we face deflation, then debt burdens on over leveraged companies and consumers will be a much greater drag on growth.

- If negative interest rates continue, they’ll force banks and insurance companies to find new business models, or slowly perish. If negative interest rates reverse, it will be a shock to a lot of overleveraged companies

- Pension funds are a looming disaster in many western countries. The government will overreact somehow when it becomes a social issue.

- Many investors, including pension funds, have rushed into illiquid alternatives such as private equity in search of higher returns. It is likely that those investments will fail to deliver the expected returns, and worse yet, they might be illiquid for longer than expected.

- ETFs have grown from obscure backwater to the default investment option for both institutional and retail. Many ETFS are invested in illiquid assets- creating the potential for a unique type of death spiral. The SEC recently made some changes to its filing requirements which might make it easier to preemptively find which ETFs are most vulnerable.

See also:

A Negative Interest Rates Thought Experiment

Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore

Dorothy in Wizard of Oz

With a negative yielding investment, the price you pay exceeds the sum that you will get back at maturity plus the income you receive in the interim. If you buy a negative yielding bond you are guaranteed to lose money. If the rate you receive on bank deposits is negative, you are guaranteed to lose money.

Negative interest rates are becoming kind of a big deal:

Most negative yielding debt is government debt, which is ironically considered “safe”, at least in first world countries. With government debt, you know what cash flows you will receive during the holding period, and what face value amount of principal you will receive upon maturity. With everything else, cash flow is uncertain and principal is always at risk. Indeed the yield on government debt functions as a proxy for the “risk free rate” , which is a critical input in financial models investors use to make strategic decisions throughout financial markets.

Conservative investors generally prefer to hold a lot of government debt in order to meet future needs. Pensions, banks, and insurance companies are required to hold a minimum percentage of their assets in government debt so they can safely meet obligations to their stakeholders.

Negative interest rates cause a lot of surprising second order impacts throughout the world impacting how people do business.

Options Pricing

The Black Scholes model is one of the pillars of modern finance. It uses the risk free rate as an input but it cannot compute when the risk free rate is negative. It requires users to calculate a logarithm. Yet the logarithm of a negative number is undefined/meaningless. Here is a paper that explored the implications in more detail. Maybe people can use the old Brownian motion models, but there isn’t going to be universal agreement right away on what to use.

Any switchover will create unintended consequences throughout the investment world . Lots of funds hold over the counter options or swaps which must be valued using models in the time between their initiation and expiration or exercise. This valuation impacts the number that appears on the statement of investors. To the extent that investors have asset allocation targets around what percent of the entity’s assets can be invested in what, this will have secondary impacts in other markets. A lot of large firms have to totally change their valuation policies which is never easy to do because valuation departments are plenty busy with their jobs as it is. Markets aren’t going to close just so they can rewrite their valuation policies.

Also, in cases where a swap or OTC option contract requires collateral to be posted as the pricing changes throughout the life of a contract, both sides of the contract need to agree on valuation methods. When interest rates are positive, Black Scholes is a noncontroversial options I doubt contractual language was written in a way that accommodate for a world where Black Scholes would completely stop working.

Currently, more banks are trading a wide number of options without a reliable price. Each bank could handle this problem by performing its own solution, but the lack of a shared approach could lead to serious legal issues.

Source

This stuff is all theoretical but it has real cash impact throughout the world. What types of risks can be hedged will impact how capital can be allocated. How capital is allocated directly impacts what ideas get funded.

Now lets consider the real world impact on different groups of investors.

Stimulating TINA

In theory, negative rates should stimulate the economy. If investors only invest in safe assets, nothing else will get funded. Retirees need income from investments to live, foundations need to earn enough to safely withdraw funds, etc etc. If the bank charges them to hold their cash, they will invest more in real estate, high yield debt, and venture capital etc. They will have to take no more risk because “there is no alternative”(TINA).

However, when you look at how negative rates will impact pensions, banks and insurance companies, its hard to escape the conclusion that they might have a destructive, rather than stimulative impact on financial markets.

Pensions

People live longer than they can work. To prevent a social catastrophe, countries have different ways of providing for old people. Pensions are a big part of the financial markets According to CFA society: Willis Towers Watson’s 2017 Global Pension Assets Study covers 22 major pension markets, which total USD 36.4 trillion in pension assets and account for 62.0% of the GDP of these economies.

In the US people pay into Social Security, which provides a bare minimum standard of living to old people. The Social Security Fund is only allowed to invest in US Treasury Securities. If Treasuries yielded negative, the Social Security Fund will erode over time, meaning it won’t be able to meet its bare minimum obligations to retirees.

Social Security by itself barely provides enough to live on. A lot of people in the US and around the world also have pensions through their jobs as well. The impacts of negative rates get more nuanced and even weirder when you consider how these work.

First of all, extremely low interest rates worsen pension deficits. Future obligations must be discounted backwards. Lower discount rate leads to higher obligations in the present day. On the other side of their balance sheet, they must make an actuarial assumption about future returns on their investments. From what I’ve seen they often make aggressive return assumptions. To try to justify higher return assumptions, they put what they can into riskier investments. To this extent pension funds are partially in the TINA Crowd.

Pensions are generally also obligated to put a certain amount of assets into “safe assets” which are the first thing to start yielding a negative rate. As a result, this negative rate will create a destructive feedback loop.

Gavekal had this story of a Dutch Pension as an example:

One day he was called by a pension regulator at the central bank and reminded of a rule that says funds should not hold too much cash because it’s risky; they should instead buy more long-dated bonds. His retort was that most eurozone long bonds had negative yields and so he was sure to lose money. “It doesn’t matter,” came the regulator’s reply: “A rule is a rule, and you must apply it.”

Thus, to “reduce” risk the manager had to buy assets that were 100% sure to lose the pensioners money.

Pension funds get caught in a feedback loop that will erode their capital base. For example say they buy a 5 year zero coupon bond at €103:

The €3 loss will reduce the market value of assets by €3. Holland also has a rule that pension funds must buy more government bonds the closer they get to being underfunded. Yet buying such negative-yielding bonds and keeping them to maturity ensures losses, making it more likely the fund will be underfunded, and so forced to buy more loss-making bonds (spot the feedback loop). Soon the fund will be distributing returns from capital, rather than returns on capital. Hence,it is not inflation that will destroy pension funds, but the mix of negative rates and rules that stop managers from deploying capital as they see fit. These protect governments, not pensioners who are forced to buy bad paper.

So negative rates will exacerbate the global retirement crisis. Oops.

Banks

What about banks? Negative rates also destroy their capital base, and leave them with less money to actually lend out in the economy. This hits at the heart of how fractional reserve banking works.

According to Jim Bianco at Bloomberg:

For every dollar that goes into a bank, some set amount (usually about 10%) must go into a reserve account to be overseen by the central bank. The rest is either lent out or used to buy securities.

In other words, the fractional reserve banking system is leveraged to interest rates. This works when rates are positive. Loans are made and securities bought because they will generate income for the bank. In a negative rate environment, the bank must pay to hold loans and securities. In other words, banks would be punished for providing credit, which is the lifeblood of an economy.

Gavekal explains how this leads to an eroding capital base (using the same 5 year zero coupon bond as the pension example above):

As a leveraged player, let’s assume it lends a fairly standard 12 times its capital. This capital has to be invested in “riskless” assets that are always liquid. In the old days, this would have been gold or central bank paper exchangeable into gold. Today, the government bond market plays the role of “riskless” (you have to laugh) asset, which has no reserve requirement. As a result, banks are loaded up with bonds issued by the local state. Now let us assume that a bank has just lost €3 on the zerocoupon bond mentioned above. The bank’s capital base will be reduced by €3. Based on the 12x banking multiplier, the bank will have to reduce its loans by a whopping €36 to keep its leverage ratio at 12. Hence, the effect of managing negative rates while also respecting bank capital adequacy rules means that the capital base can only shrink.

Insurance Companies

One of the main ways that insurance companies make money is by collecting premiums in advance of paying out any claims. Hey are able to invest these premiums, collecting a float premium. Of course they are limited in how much risk they can take with the money they are holding to pay out any possible claims. Regulators generally require them to put a certain amount in a “risk free “ asset like government debt, and the rest in riskier assets. If government debt is negative yielding, we again get to a destructive feedback loop that has major second order impacts.

From the Gavekal note:

The insurance company could raise its premium by the amount of the expected loss from holding the bond (not very commercial), or it could just underwrite less business. Either way, it will have less money to invest in equities and real estate. Simply put, either the insurance company’s clients will pay the negative rates, or the company itself will do so by increasing its risks without raising returns. This means that either the client pays more for insurance, and so becomes less profitable, or the insurance company takes a hit to its bottom line.

People will have to pay more premiums for less insurance coverage.

Long term, negative rates will exacerbate the retirement crisis and basically destroy the business models of banks and insurance companies as we know them. This doesn’t automatically mean negative interest rates can’t persist. Perhaps there are other ways to provide for old people (ie higher taxes on a shrinking economy?) Banks and insurance companies can find other ways to make money. Regulators might respond, by changing rules or creating various incentive programs.

In this post I only covered only a few of the second order impacts of negative interest rates. Negative interest rates make the capital asset pricing model give nonsensical infinite results. I think CAPM is mostly bullshit anyways, but enough people use it that it has a reflexive impact on asset pricing. Unwinding it won’t be easy. I didn’t even touch on how negative rates can screw up the plumbing of financial markets: repo markets, securities settlement , escrow etc. Not enough people have really thought this all through. Many of the assumptions that have historically driven investor behavior will no longer hold if negative rates persist.

Maybe interest rates will normalize again. It will wipe out a few of the most overleveraged players, but the financial system will recover quickly. On the other hand, if negative rate do persist, get ready for a slew of unintended consequences in places you didn’t expect.

See also:

Mysterious by Howard Marks at Oaktree

A Different Kind of Death Spiral: ETFS, Mutual Funds and Systemic Risk

The rapid growth of ETFs is one of the most significant changes to financial markets in the last decade. Total ETF AUM grew from $0.5 trillion in 2008 to over $3 trillion by the end of 2017. More remarkably, AUM of ETFs invested in illiquid sectors such as global bank loan , emerging market bonds, and global high yield bonds increased 14 fold from $10 billion 2007 to $140 billion at the end of 2017. Prior to the last financial crisis, ETFs were a relatively small niche, but these past few years it seems like every asset manager has launched an ETF. Most investors have a large portion of their retirement assets in ETFs, and many investors exclusively invest in ETFs.

This is a major systemic change from what was in place prior to the last financial crisis. Since markets go through cycles its worth asking: how will the ETF ecosystem hold up next time there is market turmoil?

ETFs have overall been a massive benefit to investors because they lowered costs. Yet as more and investors put more and more money into ETFs, there are growing signs of distortions. Some investors have pointed out how ETFs are creating bizarre valuations that are unlikely to be sustainable. Additionally, there are growing signs that the ETF structure is far more fragile than most market participants realize. These aren’t just doom and gloom conspiracies from Zero Hedge. Organizations such as the IMF, DTCC, G20 Financial Stability Board, and the Congressional Research Service have all pointed out possible risks from the unintended consequences of ETF growth.

How the ETF ecosystem works

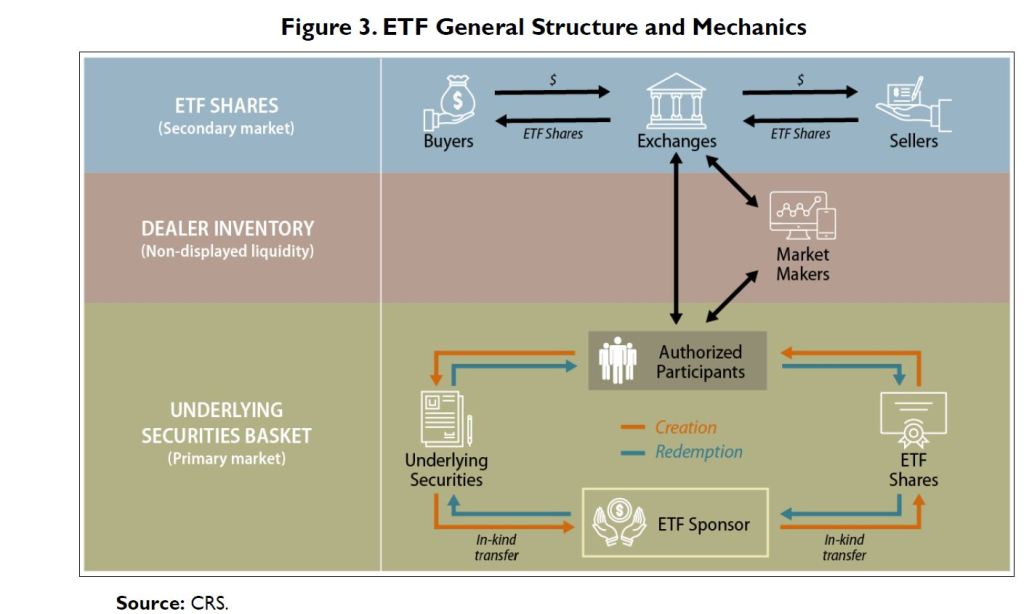

The structure and mechanics of ETFs are unique and different from mutual funds. Unlike mutual funds, ETFs generally don’t have to meet redemptions in cash. The key difference is the role of Authorized Participants (APs), and the arbitrage mechanism. The Congressional Research Service provides a handy diagram explaining the structure (Most fund sponsors have similar diagrams in their whitepapers) :

From the same CRS paper:

In a typical ETF creation process, the ETF sponsor would first publish a list of securities in an ETF share basket. The APs have the option to assemble and deliver the securities basket to the ETF sponsor. Once the sponsor receives the basket of securities, it would deliver new ETF shares to the AP. The AP could then sell the ETF shares on a stock exchange to all investors. The redemption process is in reverse, with the APs transferring ETF shares to sponsors and receiving securities.

ETF shares are created and redeemed by authorized participants in the primary market. The fund sponsors do not sell their ETF shares directly to investors; instead, they issue the shares to APs in large blocks called “creation units” that usually consist of 50,000 or more shares. The APs’ creation and redemption process often involves the purchase of the created units “in-kind” rather than in cash. This means that the shares are exchanged for a basket of securities instead of cash settlements.

The supply of ETF shares is flexible, meaning that the shares can be created or redeemed to offset changes in demand; however, only authorized participants can create or redeem ETF shares from the sponsors. A large ETF may have dozens of APs, whereas smaller ETFs could use fewer of them.

The “arbitrage mechanism” is a key feature of the ETF ecoystem. The market incentivizes APs to correct supply demand imbalances for ETFs because they can always exchange underlying shares for the securities in the portfolio and vice versa. So theoretically ETFs should not end up with discounts or premiums to NAVs like closed end funds.

Additionally, since the ETF Sponsor can redeem in kind, rather than in cash, they don’t need to sell underlying securities to meet redemption requests, like with mutual funds. Additionally, unlike with mutual funds, you get some intraday price transparency. Sometimes media commentary on “illiquid assets in liquid wrappers” mixes these up, but the nuance is important to how the respective ecosystems will react to market turmoil.

The arbitrage mechanism is a huge benefit for ETFs, and it works pretty well for deep liquid markets, like large cap stocks. Yet with less liquid assets such as leveraged loans or high yield bonds, there is reason to worry. ETFs haven’t really solved the liquidity mismatch problem. Closely related, any understanding of market history leads us to conclude that APs are unlikely to function in a falling market.

Liquidity mismatch in ETFs

Theoretically if there is a flood of selling at ETF level, APs can buy from portfolio managers, then exchange for underlying securities. However what happens if there is no bid/ask for some or all of the underlying securities?

There are several large ETFs that consist of leveraged loans and high yield bonds. A retail investor can have instant liquidity in the ETF market, and theoretically if there is an imbalance in the secondary market APs will step in and exchange ETF shares for the underlying bonds and loans. Yet these underlying assets can go days without actually trading(they are “trade by appointment”) . ETFs may be a small percentage of all outstanding bonds/loans, yet there is very little turnover of these assets, and often its difficult to get pricing. Its not clear how the market would respond if there was a macro event that caused loan prices to gap down, and investors to seek redemptions from ETFs en masse. Prior to the last financial crisis, few ETFs held high yield bonds, and no ETFs held leveraged loans.

According to the DTCC:

Some analysts assert that ETFs have become so large in certain markets that the underlying securities may no longer be sufficiently liquid to facilitate ETF creation/redemption activity during periods of stress and could result in price dislocations.

From Duke Law’s FinReg Blog:

Consider a crisis scenario where selling pressure causes underlying assets (like fixed income securities) to become illiquid and rapidly lose value prompting ETF holders to quickly sell their shares. Here market makers and APs would likely widen their bid-ask spreads to “compensate for market volatility and pricing errors.” Increased fund redemptions in the primary market could also detrimentally change the composition of the underlying portfolio basket causing APs – who no longer want to redeem ETF shares and receive, in-kind, the plummeting and illiquid securities – to withdraw from the market altogether.

Also notable, post financial crisis regulatory changes caused bond dealers to hold less inventory. This can mean less liquidity in a crisis, as this recent academic paper notes:

When an extreme crisis hits, historically, OTC market liquidity disappears. That is, no one is available to take the other side of the trade. There are simply no bids, no offers, and no trading activity in OTC markets. The recent reduction in dealer inventories means that markets will be even more volatile in the next crisis.

This is unlikely to be a problem for deep liquid markets such as large cap stocks. So any problem with popular stock index funds is likely to be resolve itself quickly But it could take a long time to unwind problems in leveraged loan and high yield bond ETFs.

Won’t the APs fix this?

Its important to emphasize that the APs have no fiduciary duty to provide liquidity. The AP will have an agreement with the fund sponsor, but the fund sponsor does not compensate the AP directly. APs can profit by acting as dealers in the secondary market, or clearing brokers, thus collecting payment for processing and creation/redemption of ETF shares from a wide variety of market participants. APs can stop providing liquidity anytime they want. In the event of a crisis it may be prudent to do so. From Duke Law:

As such, a reliance on discretionary liquidity, in the context of a crisis is inherently “fragile” since dealers and market makers will stop providing it once they start incurring losses, or their balance sheets are negatively impacted from other exposures and they can no longer bear the additional risk from providing the liquidity support

In 2013 some ETFs traded at a steep discount when Citigroup hit its internal risk limits. That was in the middle of a great bull market. What will happen if there is a serious macro problem? As a historical precedent, during the financial crisis the auction rate security market collapsed when discretionary liquidity providers exited due to turmoil.

A different kind of death spiral

There are risks for both ETFs and Mutual Funds that hold illiquid assets. However the reasons are different, and the nuances of a blow up will be different.

A mutual fund can get exemptive relief from the SEC to suspend cash redemptions in extreme circumstances. Mutual fund investors, who thought they had a daily liquidity vehicle, are left holding an illiquid asset. This happened to the Third Avenue Focused Credit fund a couple years back. This caused a short lived mini-panic in the high yield debt market. When the fund suspended cash redemptions, they paid redemptions in shares of a liquidating trust. An outside party offered to buy the shares at a 61% discount to the NAV, which had already declined sharply.

In the case of an ETF it’s a bit more complicated. The death spiral could simply take the form of a self reinforcing feedback loop. Retail investors would be able to exit, albeit at a steep discount. APs would sell underlying securities that they can sell, causing prices to plummet, causing further retail panic. Some assets are more illiquid than others, and once once the dust settles, the ETF will be left holding the most illiquid and opaque assets.

During the past few years we’ve seen a few tremors. There was the short incident in 2013 mentioned above. In May 2010 and August 2015 there were large one day price swings in more liquid parts of the ETF market probably caused by algorithms. In February 2018 there was the great VIX blowup/ “volmageddon”. The VIX example was a bit different because it involved very unique derivatives, but I think the bigger more interesting problems could be in the credit space. In 2018Q4 there was some volatility in the credit space, and MSCI noted ETFs appeared to have a mild impact on bid/ask spreads. Yet by historical standards what happened in 2018Q4 was very minor.

These examples all occurred during a long bull market. What will happen in the next 2008 type scenario? I Still need to look more into how they might actually unwind.

So what can an investor do?

Most ETFs(and mutual funds) will probably be fine. During a crisis there might be temporary NAV discounts even for large cap index funds and lots of panic selling all around. Mutual fund investors will redeem at the worst possible time, and funds will sell shares into a falling market to meet these requests. Headlines will be full of doom and gloom. The prudent thing for most investors will be to ignore it all. Continue dollar cost averaging across the decades to retirement and beyond.

Nonetheless, investors holding some of the more esoteric, illiquid ETFs and mutual funds could be in for an unpleasant surprise and possible permanent capital impairment. Even though these potentially problematic funds are a small portion of the overall market, there is likely to be systemic contagion, as the IMF noted.

I’ve purchased some cheap puts on more fragile ETFs(mainly high yield bond and leveraged loan) although the lack of an imminent catalyst means that the position size needs to be small. I’ll be looking more closely at the way these different types of structures are unwound, since there are likely to be some major time sensitive opportunities next time it occurs.

Other possible case studies of the unwinding of illiquid assets in liquid wrappers:

- UK open end commercial property funds during Brexit vote

- Auction rate securities during financial crisis

- Interval Funds during the financial crisis.

- Other mutual fund redemption suspensions and ETF tremors?

See also:

Thinking and Applying Minsky

Hyman Minsky developed a framework for understanding how debt impacts the behavior of the financial system, causing periods of stability to alternate with periods of instability. Stability inevitably leads to instability. Minsky identified three types of financing: Hedge financing, speculative financing, and ponzi financing. It seems some people only remember Minsky every so often when there is a financial crisis, but the framework is useful in all seasons.

Hedge Financing

An asset generates enough cash flow to fulfill all contractual payment obligations. For example, a conservatively leveraged rental property that generates enough rent to pay down the entire mortgage over time, regardless of the change in quoted property prices. Or a company that issues some bonds, then pays them back using cash flow from the business Generally hedge financing units have a lot of equity down. Even a market crash, will not cause an investor to suffer permanent capital impairment if they only use hedge financing. The equity holder who uses hedge financing will never depend on the capital markets.

Speculative Financing

An asset generates enough cash flow to fulfill all debt payments, but not the full principal amount. In this case debt must be rolled over, or the asset must be sold, in order to pay back the full amount. For example, a rental property financed with some sort of balloon payment structure that generates enough cash flow to pay off mortgage payments up until the balloon payment at the end. When the balloon payment comes due, the investor must roll over the debt or sell the asset. An investor ttat uses speculative financing is dependent on capital markets. If there is a delay or a problem in refinancing, they could lose their investment.

Ponzi Financing

This is basically “greater fool” investing. Ponzi financing means there is so much leverage n an asset, that the investment must be refinanced, or sold at a higher price quickly, otherwise the entire investment is lost. Sometimes property purchases will be financed with shorter term bridge loan. If the bridge loan can’t be refinanced with longer term mortgage, the investor is out of luck. Towards the end of the market cycle, many companies will be issuing bank loans or bonds that can only be repaid by refinancing. If their unable to refinance, they go bankrupt.

Use of ponzi financing means the investor is highly dependent on capital markets. The slightest disruption in capital markets or change in interest rates/inflation results in a large capital loss.

Junk bonds are not inherently bad. A higher interest rate can in many cases compensate for greater risk, especially across a portfolio of non correlated investments. Howeve, duringthe junk bond era, many companies

Similarly securitization is not inherently bad. It can allow capital to flow more effeiciently. But often banks would end up aggressively securitizing, with the need to sell the loans they made quickly. But if they weren’t able to resell they couldn’t hold the loans. This happened to Nomura during the Asian financial crisis, as vividly told in this Ethan Penner interview.

Ponzi in this case is not illegal activity, just extremely risky. Of course those investors who finance their activities ponzi style often end up feeling the need to commit illegal acts. The Minsky Kindleberger model is useful here.

The cycle repeats

During a recession is very difficult to get any debt financing that is not “hedge financing”. Lenders are scarred from the last cycle, and there is a paucity of available risk capital. But a price rise, and investors get more comfortable, more and more financing becomes ponzi units In fact. Lenders may lower their standards and become more accepting of ponzi units.

Throughout the market cycle, more and more financing is ponzi units. Eventually there is no greater fool to sell to. When many ponzi units are forced to sell at once, it eventually leads to a collapse in values. This is how stability inevitably leads to stability. The cycle repeats.

How to apply this?

To protect my capital, I look try to mainly expose myself to hedge financing, with a small amount of speculative financing. I position my portfolio so that I don’t need to refinance anything or sell anything in a rush. When I invest in leveraged companies with speculative or ponzi financing, I make it small position(always in some sort of limited liability structure), and generally won’t average down much if at all. Additionally, when I notice an increase in ponzi financing in the markets, I become more cautious.

Leverage, like liquor , must be consumed carefully if at all.

See also:

Sam Zell: Poet laureate of contrarians and dumpster divers

Sam Zell is the patron saint of contrarians and poet laureate of dumpster divers. He has one of the best track records of any real estate or distressed asset investor, and helped pioneer the use of REITs, NOLs, and other key strategies and structures. His excellent autobiography is a valuable lens from which to understand the last 50 years of economic history.

Although he built up his reputation in off the beaten path markets, his sense of macro timing is also surreal. He loaded up on multifamily properties at the bottom of the market in the 1970s. He sold out of a large portion of his holdings near the top of the market in 2007(although that story was a bit more nuanced than I realized prior to reading the book).

Here are my notes and highlights from the book:

A full throttle opportunist

This isn’t a dress rehearsal. I try to live full throttle. I believe I was put on this earth to make a difference, and to do that I have to test my limits. I look for ways to do that every day. After all, I think it was Confucius who said, “The definition of a schmuck is someone who’s reached his goals.” It’s up to me to keep moving the end zone, and go for greatness.

….At some point the guy I was sitting next to turned to me and asked, “So what do you do?” I replied, “I’m a professional opportunist.” And that has been my response to that question ever since.

History

Zell’s Jewish parents were on one of the last trains out of Poland, just hours before the Nazi’s bombed the train tracks and took over. Many of his ancestors perished in concentration camps. His parents reminded him of this, and it appears to have had a significant impact on his world view

Did you ever wonder how the Jews allowed the Nazis to come into Poland without taking action? I asked my father that when I was little, and I’ll never forget what he said. The Jewish community in Poland at the time was extraordinarily myopic—it had little idea what was going on in the world. And it cost most of them the ultimate price. In contrast, my father’s macro understanding of world events and the conviction to act saved the lives of my family. I apply the same strategy on a much less life-and-death scale. I rely on a macro perspective to identify opportunities and make better decisions, both in my investment activity and in leading my portfolio companies. I am always questioning, always calculating the implications of broader events. How will worldwide depressed currencies affect capital flows and world trade? Does it create opportunity for international expansion among multinational companies? What real estate needs will they have? How can we get a first-mover advantage into new markets? And on and on.

Avoiding the crowd

Zell was clearly unafraid of career risk. Several times in his career he safely sat out major bubbles, and pounced later when it all burst.

The industry has a long history of overbuilding when there’s easy money, without regard for who will occupy those spaces once they’re built. At the same time that construction cranes were dotting the horizon of every major city, the country was just starting to tip into a recession. Supply was going up and prospects for demand were not good. I was certain that we were headed toward a massive oversupply and a crash was coming. That’s when I just said, “Stop.” I was done. I stopped buying assets, started accumulating capital, and got ready for what I was sure would be the greatest buying opportunity of my career thus far. My thesis was that over the next five years, we would have the opportunity to make a fortune by acquiring distressed real estate. So I established a property management firm, First Property Management Company (FPM), to focus on distressed assets. Everyone thought I was nuts. After all, occupancies were still over 90 percent. Absorption was high. Companies were hiring. It was one of many times I would hear people tell me that I just didn’t understand.

I didn’t listen. I just stepped aside while the music was still playing. It was the biggest risk I had taken to date in my career. After all, I had a stable of investors by then. What would they think if I bowed out and the end didn’t come? That would mean I was forgoing a lot of upside for them. It was a true test of my conviction. But I had to follow the logic of supply and demand. Turns out I was right. Less than one year later, in 1974, the market crashed. Hard.

Overnight, we were buying assets at 50 cents on the dollar. At the time, financial institutions did not have to mark to market. In other words, they didn’t have to adjust the book value of their assets to the current market value those assets could actually sell for. If you were an insurance company, instead of marking to market, you could avoid taking a hit

Avoiding competition

By being contrarian, Zell avoided competition.

In 1980, Bob and I sat down and listed the reasons we didn’t like where the real estate market was headed. First, the key to our prior success had been an inefficient market. The real estate industry had always been fragmented, with valuations and projections that often varied widely. That started changing rapidly with the debut of Hewlett-Packard’s financial calculator. All of a sudden, any owner could hire an MBA with an HP-12C to run ten years of cash flows, none of which considered recessions or rent dips, and make an elaborate and sophisticated case for investment—and a bunch of eager investors would show up to check out the property.

That was not an arena we wanted to compete in. Second, up until then, lenders made long-term, fixed-rate, nonrecourse loans. But as a result of inflation in the 1970s, they got scared and switched to short-term, floating-rate loans. We believed the real money in real estate came from borrowing long-term, fixed-rate debt in an inflationary scenario that ultimately depreciated the value of the loan and increased the position of the borrower. Finally, we had always looked at the tax benefits of real estate as what you got for the lack of liquidity. All of a sudden, sellers were including a value for tax benefits in their asset pricing. So we said, “If we’ve been as successful in real estate as we have been, aren’t we really just good businessmen? And if we’re good businessmen, then why wouldn’t the same principles that apply to buying real estate apply to buying anything else?” We checked the boxes—supply and demand, barriers to entry, tax considerations—all of the criteria that governed our decisions in real estate, and didn’t see any differences. So we set a goal that we would diversify our investment portfolio to be 50 percent real estate and 50 percent non–real estate by 1990.

We narrowed our universe by targeting good asset-intensive companies with bad balance sheets, a thesis similar to real estate. We liked asset-intensive investments because if the world ended, there would be something to liquidate. The low-tech manufacturing and agricultural chemical industries were perfect fits for us—the former driven by Bob with his expertise in engineering and passion for anything mechanical.

…….

I’ve spent my career trying to avoid its destructive consequences. Competition skews people’s assessments; as buyers get competitive, the demand for assets inflates pricing, often beyond reason. I jokingly tell people that competition is great—for you. Me, I’d rather have a natural monopoly, and if I can’t get that, I’ll take an oligopoly. Not long after we got involved with GAMI,

Micro Opportunities in Macro Events

As an investor, Zell has a unique way of combining macro insights with bottom up research.Several examples in the book highlight this. He was “all about seeing micro opportunities in macro events. For example:

In this case, the macro event was legislation similar to the impact of the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 on NOLs. But I find implications for opportunity everywhere—in world events, economic news, and conversations. I’ve always been on the lookout for big-picture influencers and anomalies that will direct the course of industries and companies. But first-mover advantage requires conviction. While the rest of the radio industry was deliberating about what the telecom bill meant and how it would be implemented and whether it was a good change or a bad change, we moved and bought up

Zell’s abiliy to see the big picture gave him an edge in international investing. He was the first gringo in town buying real estate in a lot of the bigger emerging market stories of the past few decades:

This is our primary premise in international investing—the transformation of businesses into institutional platforms. We started in Mexico, then went to Brazil. Then to Colombia, India, and China. So far we’ve brought about thirty companies in fifteen countries along for the ride, with four IPOs. I’m drawn to emerging markets because of their built-in demand. I’ve always believed in buying into in-place demand rather than trying to create it. To me, international investing is largely a story of demography. Just look at population growth. Most of the developed countries (e.g., U.K., France, Japan, Spain, Italy) have aging populations and are ending each year with flat or negative population growth rates. For instance, we don’t spend much time looking at Western Europe. It’s Disneyland. It’s great for wine and castles and cheese, but there’s no growth there. Further, Europe has the largest population of pensioners in the world. The number of retirees who don’t work is close to double what we have in the U.S. and most of those European countries fund each year’s pensions from taxes. It begs the question, with a shrinking workforce where will that money come from? In contrast, most of the emerging markets (e.g., India, Mexico, Colombia, South Africa, Brazil) have younger populations and higher growth rates. And while growth rates across the board have fallen off a cliff opportunity there as well. In particular, we are drawn to Mexico. After the Fukushima nuclear disaster occurred in Japan in 2011, nearly every multinational executive I talked to was bemoaning the cost of delays and availabilities in exports coming out of Asia. I couldn’t help but think that companies would not want to get caught in that type of scenario again, so they would be looking for an alternative manufacturing option closer to home. The only logical place was Mexico. Also, Chinese labor costs were steadily rising and eroding the margin for U.S. companies to manufacture there. So we invested in a Mexican warehouse and logistics company to support what I believed to be a pretty good bet on future growth. Sure enough, within four years, Mexico was in a manufacturing boom with a double-digit increase in exports from Mexican factories. We continue to view opportunity on a global scale. I see international investing as a challenge of connecting multiple dots to reach a conclusion. My job has always been to identify the dots we should pay attention to as well as the incentives that will connect them—all to get maximum possible results

See also:

- One of Zell’s early breaks was buying massive amounts of apartments at the bottom of the market in the late 70s He outlined this thesis classic article : “The Grave Dancer”

- Sam Zell Looks Back

- A dozen things I’ve learned from Sam Zell

Fistful of Lira

While packing for my redeye flight to Istanbul tonight, I remembered the last time I had travelled to Turkey around 6 years ago. After getting sort of stranded in Kazakhstan for a day, I ended up wandering back alleys of Istanbul talking to questionable people in the non-bank financial service sector.

A planning error left me with no choice but to run an experiment on the fringes of the global forex market.

At the time, I was working at an investment bank in China, but I got a week off for a some sort of Communist Party workers holiday in October. My then girlfriend now wife was a grad student in the US. We decided to meet in Turkey for a little getaway.

As I prepared for the trip I was flush with RMB(Chinese yuan), but short on dollars and Euros(1). None of the banks in Beijing I went to would directly change RMB to Turkish Lira. Plus all them had silly wide bid-ask spreads on RMB/USD or RMB/EUR transactions. No point in changing here I thought, I’ll just change once when I get to Turkey. Turns out that was a rookie mistake.

I was on the Air Astana flight from Beijing to Istanbul with a layover in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Checking in was a bit of a debacle. I had to wait in a long line behind migrant laborers who had absurdly large quantities of luggage to check, much of it in non-traditional suitcases (ie barely sealed cardboard boxes).

The guy in front of me in the line to check in was about 6 foot 4, bald, big boned, with the look of a football referee who let himself go. After some sort of commotion at the front of the line , he turned around, smiled and said in a baritone, probably Russian Accent: “Almaty airlines ,this always happens. “

The flight was delayed a few hours but it ultimately did take off. However we were late enough that I missed my connecting flight. I had a day to wait for the next flight to Istanbul.

Almaty airport wasn’t fancy, but it was no worse than many of the small airports I’ve been to around the globe. I went to a cafe to get some food.

Turns out they wouldn’t accept RMB. No problem I thought, and I walked over to the one moneychanger accessible from the terminal I was at.

Turns out they wouldn’t change RMB at all.

I went to the ATM, and it wouldn’t accept my card for some reason.

For amusement I tested if any of the shops there would take RMB. None would.

At least I got a lot of reading done passing the time with no money to entertain myself in the airport for a day. I don’t remember what the meal was on the next leg of the flight, but I remember it was quite delicious.

When I got to Istanbul, and ran into identical forex issues with shops, moneychangers, and ATMs.(2)

So I wandered the streets going into moneychangers asking to change money. Even banks with China origins wouldn’t do it. Finally one money changer looked surprised, and asked “how much,” as he motioned me over towards the other end of the counter.

I answered him, then he took out a pen and a piece of scrap paper, and started to draw a map.

It was a long journey. As I recall, I had to go to the far end of one of the subway lines, then walk for about 15 minutes. Finally I found a shop that would change RMB. But their rate was horrible so I said I’d be right back.

I finally found another one a block over with a much better rate. I was relieved to at last clutch a fistful of Lira.

The rest of the trip went smoothly. Of course those days were before Erdogan, um “changed” (3).

This time I’m going back to Istanbul, with a mix of USD and Euro I’m excited to enjoy deeply discounted falafel, and drink coffee while working from a deck on the Asia side of the bosphorus, with a perfect view of the river, and Europe on the other side. I won’t have time to explore the far ends of the subway lines since I’ll only be in Istanbul for a day. After that I’ll be going to Sofia Bulgaria and working there for a week.

…

(1)When if ever will the RMB be a global currency? I don’t know. My general view on currencies is I never make pure directional bets. I just try to avoid getting killed by sudden changes. This basically means cautious sizing of any position that is exposed to fringe markets. Smart operational decisions have real alpha implications in these areas as well I guess you can say I learned this on the streets, the hard way.

Anyways, while there is now a surplus of superficial media coverage of China’s One Belt One Road policy,few people are talking about the capital markets implications. China is basically throwing money at every country to its west all the way to Europe, with a potentially huge impact of the smaller countries. What I find interesting is that most of it is going to be financed with yuan denominated debt, not dollar denominated debt. Combined with a yuan denominated oil futures contract hitting the market, One Belt One Road will result in a lot more financial market activity in yuan rather than dollars. I would still consider yuan internationalization(and a decline in the dollars status) a bit of a long shot near term, but these recent changes make it a lot more plausible over the next decade. At the very least there will soon be a lot more funky securities denominated in yuan(many probably, ahem, distressed and deeply discounted), so it makes sense to get comfortable with custody and banking issues involving the currency.

(2) My ATM card ended up getting flagged with a security alert for suspected fraud, which I was later able to resolve.

(3) Much as been said about his more populist tendencies. I also find it amusing how non-populist policies have had unintended consequences contributing to the current crisis. For example, the government incentivized small and medium sized companies to borrow in non-Lira currencies, by loosening restrictions on loans over a threshold(IIRC, $5 million). This part of the economy is seriously hurting now. Alas there will be some fun picking in the distressed debt space before too long.

Big dam frontier market bond offerings, low dam yields

Credit markets are crazy, from US buyouts, to frontier market bond offerings.

Buffett released the annual Berkshire letter this past weekend, and it contained a number of gems as usual, although it was shorter than the typical letter.

Petition’s excellent distressed credit focused newsletter last week pointed out that Buffett’s concerns about high M&A prices were:

affirmation of a number of macro themes that ought to portend well for distressed players in a few years: (i) excess capital supply, (ii) resultant inflated asset values, (iii) lack of discipline, and (iv) over-leverage.

The big dam indicator

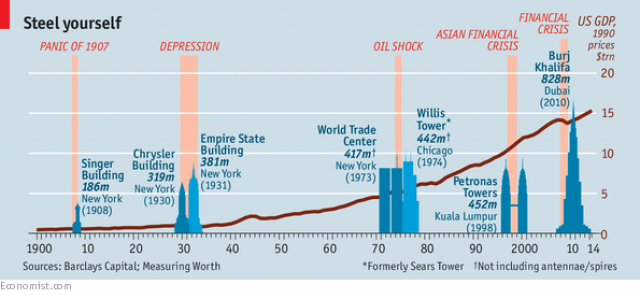

The loose credit has spread to frontier market bond offerings as well. Tajikistan, a country with $7 billion in annual GDP in September raised $500 million of debt at 7.125% for 10 years. Tajikistan had no problem raising this capital. In fact funds put in $4 billion in bids for the $500 million in paper. Tajikistan will use this capital used for the Rogun barrage project, which involves building the world’s largest hydroelectic dams. Building large buildings tends to correlate with hubris, and bubbles(although the empirical evidence around causality is loose), as many have noted:

More frontier market fun

Is credit really the smart money?

Conventional wisdom holds that credit markets are “smart institutional money” that sees problems faster than equity markets that are full of less sophisticated retail investors. I question whether that is still empirically true. Retail investors now own large portions of the credit market, including high yield. Credit markets appear to be distorted by a combination of indexation and a reach for yield. Its possible that bonds trading at par can be a false comfort signal for an equity investor looking at a highly leveraged company, because in many recent cases equity markets have been faster to react to bad news.

Retail ownership of credit markets.

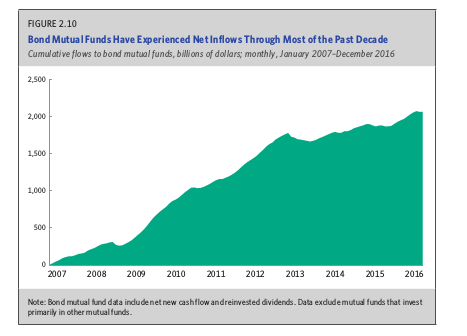

However you slice and dice the data, there is clearly a lot more retail money in credit than there was a decade ago. The media mostly reports on noisy weekly or monthly flows, even though there has been a clear long term change.

Bond funds in general have experienced dramatic inflows over the past decade:

Source: ICI Fact Book 2017

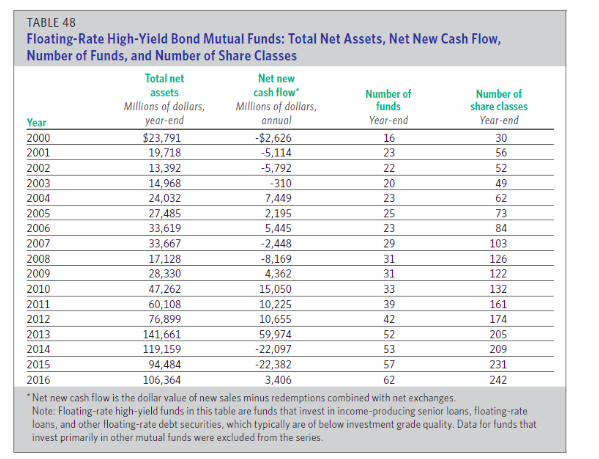

The issues becomes more serious when you look just at the high yield part of the market. Boaz Weinstein of Saba Capital estimated that between ½ or ⅓ of junk bonds are owned by retail investors in the current market. The WSJ cited Lipper data that says mutual fund ownership of high yield bonds/loans is $97 billion today vs $18 billion a decade ago. ICI slices the data differently, and comes up with a much nosier data set for just floating rate unds, indicating large outflows in 2014 and 2015. However it shows net assets in high yield bond funds up 3x compared to 2007, and the total number of funds up over 2x during that time.

Source: ICI Fact Book 2017

Its not just mutual funds either- there are now more closed end type fund structures that market towards retail investors. BDCs experienced a fundraising renaissance through 2014, and are now active in all parts of the high yield credit markets- from large syndicated loans to lower middle market. Closely related, before the last financial crisis, ago there was minimal retail ownership of CLO equity tranches, but now there are a few specialist funds, and a lot of BDCs have big chunks of it as well. Oxford Lane and Eagle Point were sort of pioneers in marketing CLO investments to retail investors but many others have followed. Interval funds are a tiny niche, but over half the funds in registration are focused on credit. It seems just about every asset manager is cooking up a direct lending strategy. The illiquid parts of the credit market are harder to quantify, but there has been a clear uptick in retail investor exposure since before the financial crisis. The marginal buyer impacting pricing is increasingly likely to be a retail investor rather than an institution.

Retail investors to exhibit more extreme herding behavior. According to Ellington Management Group:

This feedback loop between asset returns and asset flows has magnified the growth of the high yield bubble.

Capital Distortions

Its pretty easy to make a loan, its much harder to get paid back.