Tagged: Distressed Debt

A Different Kind of Death Spiral: ETFS, Mutual Funds and Systemic Risk

The rapid growth of ETFs is one of the most significant changes to financial markets in the last decade. Total ETF AUM grew from $0.5 trillion in 2008 to over $3 trillion by the end of 2017. More remarkably, AUM of ETFs invested in illiquid sectors such as global bank loan , emerging market bonds, and global high yield bonds increased 14 fold from $10 billion 2007 to $140 billion at the end of 2017. Prior to the last financial crisis, ETFs were a relatively small niche, but these past few years it seems like every asset manager has launched an ETF. Most investors have a large portion of their retirement assets in ETFs, and many investors exclusively invest in ETFs.

This is a major systemic change from what was in place prior to the last financial crisis. Since markets go through cycles its worth asking: how will the ETF ecosystem hold up next time there is market turmoil?

ETFs have overall been a massive benefit to investors because they lowered costs. Yet as more and investors put more and more money into ETFs, there are growing signs of distortions. Some investors have pointed out how ETFs are creating bizarre valuations that are unlikely to be sustainable. Additionally, there are growing signs that the ETF structure is far more fragile than most market participants realize. These aren’t just doom and gloom conspiracies from Zero Hedge. Organizations such as the IMF, DTCC, G20 Financial Stability Board, and the Congressional Research Service have all pointed out possible risks from the unintended consequences of ETF growth.

How the ETF ecosystem works

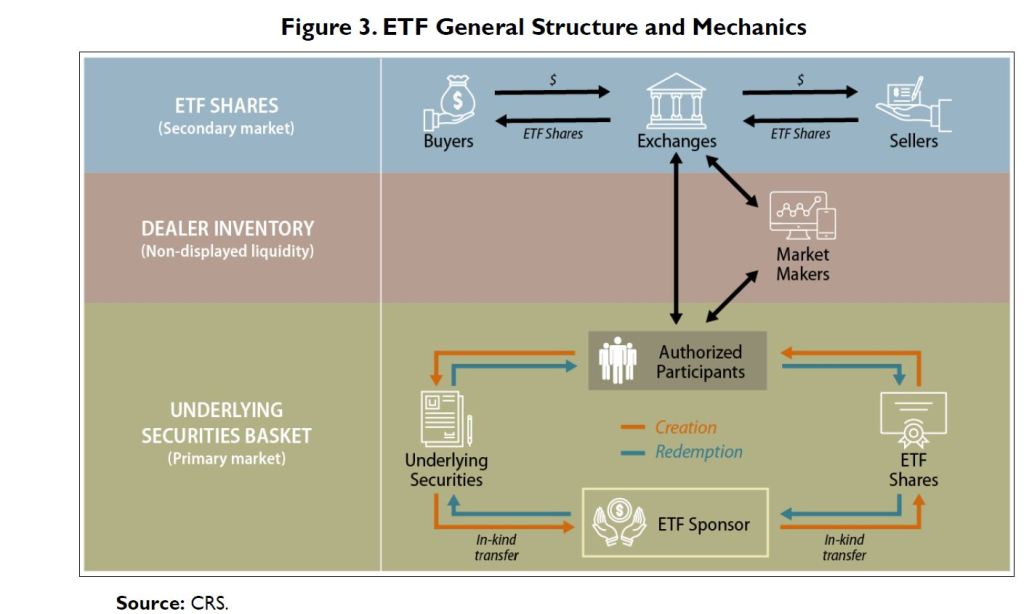

The structure and mechanics of ETFs are unique and different from mutual funds. Unlike mutual funds, ETFs generally don’t have to meet redemptions in cash. The key difference is the role of Authorized Participants (APs), and the arbitrage mechanism. The Congressional Research Service provides a handy diagram explaining the structure (Most fund sponsors have similar diagrams in their whitepapers) :

From the same CRS paper:

In a typical ETF creation process, the ETF sponsor would first publish a list of securities in an ETF share basket. The APs have the option to assemble and deliver the securities basket to the ETF sponsor. Once the sponsor receives the basket of securities, it would deliver new ETF shares to the AP. The AP could then sell the ETF shares on a stock exchange to all investors. The redemption process is in reverse, with the APs transferring ETF shares to sponsors and receiving securities.

ETF shares are created and redeemed by authorized participants in the primary market. The fund sponsors do not sell their ETF shares directly to investors; instead, they issue the shares to APs in large blocks called “creation units” that usually consist of 50,000 or more shares. The APs’ creation and redemption process often involves the purchase of the created units “in-kind” rather than in cash. This means that the shares are exchanged for a basket of securities instead of cash settlements.

The supply of ETF shares is flexible, meaning that the shares can be created or redeemed to offset changes in demand; however, only authorized participants can create or redeem ETF shares from the sponsors. A large ETF may have dozens of APs, whereas smaller ETFs could use fewer of them.

The “arbitrage mechanism” is a key feature of the ETF ecoystem. The market incentivizes APs to correct supply demand imbalances for ETFs because they can always exchange underlying shares for the securities in the portfolio and vice versa. So theoretically ETFs should not end up with discounts or premiums to NAVs like closed end funds.

Additionally, since the ETF Sponsor can redeem in kind, rather than in cash, they don’t need to sell underlying securities to meet redemption requests, like with mutual funds. Additionally, unlike with mutual funds, you get some intraday price transparency. Sometimes media commentary on “illiquid assets in liquid wrappers” mixes these up, but the nuance is important to how the respective ecosystems will react to market turmoil.

The arbitrage mechanism is a huge benefit for ETFs, and it works pretty well for deep liquid markets, like large cap stocks. Yet with less liquid assets such as leveraged loans or high yield bonds, there is reason to worry. ETFs haven’t really solved the liquidity mismatch problem. Closely related, any understanding of market history leads us to conclude that APs are unlikely to function in a falling market.

Liquidity mismatch in ETFs

Theoretically if there is a flood of selling at ETF level, APs can buy from portfolio managers, then exchange for underlying securities. However what happens if there is no bid/ask for some or all of the underlying securities?

There are several large ETFs that consist of leveraged loans and high yield bonds. A retail investor can have instant liquidity in the ETF market, and theoretically if there is an imbalance in the secondary market APs will step in and exchange ETF shares for the underlying bonds and loans. Yet these underlying assets can go days without actually trading(they are “trade by appointment”) . ETFs may be a small percentage of all outstanding bonds/loans, yet there is very little turnover of these assets, and often its difficult to get pricing. Its not clear how the market would respond if there was a macro event that caused loan prices to gap down, and investors to seek redemptions from ETFs en masse. Prior to the last financial crisis, few ETFs held high yield bonds, and no ETFs held leveraged loans.

According to the DTCC:

Some analysts assert that ETFs have become so large in certain markets that the underlying securities may no longer be sufficiently liquid to facilitate ETF creation/redemption activity during periods of stress and could result in price dislocations.

From Duke Law’s FinReg Blog:

Consider a crisis scenario where selling pressure causes underlying assets (like fixed income securities) to become illiquid and rapidly lose value prompting ETF holders to quickly sell their shares. Here market makers and APs would likely widen their bid-ask spreads to “compensate for market volatility and pricing errors.” Increased fund redemptions in the primary market could also detrimentally change the composition of the underlying portfolio basket causing APs – who no longer want to redeem ETF shares and receive, in-kind, the plummeting and illiquid securities – to withdraw from the market altogether.

Also notable, post financial crisis regulatory changes caused bond dealers to hold less inventory. This can mean less liquidity in a crisis, as this recent academic paper notes:

When an extreme crisis hits, historically, OTC market liquidity disappears. That is, no one is available to take the other side of the trade. There are simply no bids, no offers, and no trading activity in OTC markets. The recent reduction in dealer inventories means that markets will be even more volatile in the next crisis.

This is unlikely to be a problem for deep liquid markets such as large cap stocks. So any problem with popular stock index funds is likely to be resolve itself quickly But it could take a long time to unwind problems in leveraged loan and high yield bond ETFs.

Won’t the APs fix this?

Its important to emphasize that the APs have no fiduciary duty to provide liquidity. The AP will have an agreement with the fund sponsor, but the fund sponsor does not compensate the AP directly. APs can profit by acting as dealers in the secondary market, or clearing brokers, thus collecting payment for processing and creation/redemption of ETF shares from a wide variety of market participants. APs can stop providing liquidity anytime they want. In the event of a crisis it may be prudent to do so. From Duke Law:

As such, a reliance on discretionary liquidity, in the context of a crisis is inherently “fragile” since dealers and market makers will stop providing it once they start incurring losses, or their balance sheets are negatively impacted from other exposures and they can no longer bear the additional risk from providing the liquidity support

In 2013 some ETFs traded at a steep discount when Citigroup hit its internal risk limits. That was in the middle of a great bull market. What will happen if there is a serious macro problem? As a historical precedent, during the financial crisis the auction rate security market collapsed when discretionary liquidity providers exited due to turmoil.

A different kind of death spiral

There are risks for both ETFs and Mutual Funds that hold illiquid assets. However the reasons are different, and the nuances of a blow up will be different.

A mutual fund can get exemptive relief from the SEC to suspend cash redemptions in extreme circumstances. Mutual fund investors, who thought they had a daily liquidity vehicle, are left holding an illiquid asset. This happened to the Third Avenue Focused Credit fund a couple years back. This caused a short lived mini-panic in the high yield debt market. When the fund suspended cash redemptions, they paid redemptions in shares of a liquidating trust. An outside party offered to buy the shares at a 61% discount to the NAV, which had already declined sharply.

In the case of an ETF it’s a bit more complicated. The death spiral could simply take the form of a self reinforcing feedback loop. Retail investors would be able to exit, albeit at a steep discount. APs would sell underlying securities that they can sell, causing prices to plummet, causing further retail panic. Some assets are more illiquid than others, and once once the dust settles, the ETF will be left holding the most illiquid and opaque assets.

During the past few years we’ve seen a few tremors. There was the short incident in 2013 mentioned above. In May 2010 and August 2015 there were large one day price swings in more liquid parts of the ETF market probably caused by algorithms. In February 2018 there was the great VIX blowup/ “volmageddon”. The VIX example was a bit different because it involved very unique derivatives, but I think the bigger more interesting problems could be in the credit space. In 2018Q4 there was some volatility in the credit space, and MSCI noted ETFs appeared to have a mild impact on bid/ask spreads. Yet by historical standards what happened in 2018Q4 was very minor.

These examples all occurred during a long bull market. What will happen in the next 2008 type scenario? I Still need to look more into how they might actually unwind.

So what can an investor do?

Most ETFs(and mutual funds) will probably be fine. During a crisis there might be temporary NAV discounts even for large cap index funds and lots of panic selling all around. Mutual fund investors will redeem at the worst possible time, and funds will sell shares into a falling market to meet these requests. Headlines will be full of doom and gloom. The prudent thing for most investors will be to ignore it all. Continue dollar cost averaging across the decades to retirement and beyond.

Nonetheless, investors holding some of the more esoteric, illiquid ETFs and mutual funds could be in for an unpleasant surprise and possible permanent capital impairment. Even though these potentially problematic funds are a small portion of the overall market, there is likely to be systemic contagion, as the IMF noted.

I’ve purchased some cheap puts on more fragile ETFs(mainly high yield bond and leveraged loan) although the lack of an imminent catalyst means that the position size needs to be small. I’ll be looking more closely at the way these different types of structures are unwound, since there are likely to be some major time sensitive opportunities next time it occurs.

Other possible case studies of the unwinding of illiquid assets in liquid wrappers:

- UK open end commercial property funds during Brexit vote

- Auction rate securities during financial crisis

- Interval Funds during the financial crisis.

- Other mutual fund redemption suspensions and ETF tremors?

See also:

How much due diligence is enough?

“They can’t touch me. I do my homework”

-John Boyd

How much investment due diligence is enough? How much is too much?

The amount of research an investor should do before making an investment depends on three factors: 1) Size of Position 2) Illiquidity of position, and 3) Contrary nature of position.

The Kelly Criterion is a good heuristic, although in real life we never know exact probabilities. Most investments will succeed or fail on one or two factors. The key is to identify those and understand them better then the person selling to us. Anything beyond that is just for fun. Indeed a lot of investors really like to dig. But the 80/20 rule applies. Think jiujitsu not powerlifting.

Position Size

Position sizing is part math and part psychology. The bigger a position, the more a person has to check and double check. This isn’t just a number in a spreadsheet. Conduct a premortem. What is the maximum pain you can take? The only way to survive a large position going against you is to have the confidence in your research.

Its critical not to get causation wrong here. If “concentration” is part of one’s identity as an investor, there is a major risk confirmation bias will takeover and more research will just make them more sure of a false idea. Remember smarter people are actually at greater risk of confirmation bias.

If the facts lineup, it might make sense to “go for the jugular”.

Illiquidity

For most individual investors, illiquidity is a secondary concern. Nonetheless an investor must consider it. An investor can easily sell a widely traded stock or ETF. But for illiquid positions, an investor needs to learn that information ahead of time.

Decisions that are easy to reverse can be made quickly. Decisions that are difficult or impossible to reverse require more analysis up front.

Contrarian nature

Markets are usually right. The more out of consensus a view is, the more data and analysis an investor must have to back it up. “Who is on the other side?” is probably the most important question in investing. I’m only comfortable if I understand the contrary position better than people who hold it.

Active investing requires active thinking.

With investment research an hour of active critical thinking is worth more than a week of passive reading

Techniques of due diligence depend on what’s available, and also on an individual personality. Some people are good at plowing through footnotes or analyzing sentiment data, others are highly skilled at interviewing industry experts. Since computers read 10-Ks the minute they come out, its essential to get creative with due diligence, but this does not mean digging for the sake of digging.

Example:

I was researching, a venture capital focused business development company (BDC) liquidation. Its investments holdings consisted of preferred stock in 11 venture stage companies, with most of the value concentrated in the top five holdings.

Although there was limited publicly available information on the financial condition or valuation of each individual holding, the filings disclosed the aggregate range and average of the metrics and assumptions used by the company in the valuation process to arrive at fair value of Level 3 Assets on the financial statements. My interest was piqued when I noticed that other public BDCs that owned some of the same asset were marking them at much higher prices. Nonetheless, I needed to verify the viability, and growth potential of the main underlying businesses.

I approached this issue from multiple angles:

One of the company’s largest assets was preferred stock in a company that operated a dating site. With permission from my wife, I set up a fake profile to see how the interface of the website and app worked, and to verify that there were indeed a large number real people using it in my area, and a few other cities I checked. This helped me corroborate information from user reviews I had read.

The company owned stock in a highly specialized medical testing startup. I reviewed the background of top employees on LinkedIn, university websites, and various scientific journals. Additionally I discussed the business idea with friends in academia. They verified that the idea had a reasonable chance of working, and would require an advanced degree to replicate.

Accounting rules gave management ample discretion on how to report the holdings on the balance sheet. I carefully reviewed everything they had disclosed about their valuation process, and tracked changes in language between different filings over time.

I also contacted the management of the BDC, and was able to reach the people in charge of the valuation process on the whole portfolio. They helped me understand the facts they were using to justify the valuations supplementing my careful reading of the public disclosure. The conversation verified that the BDC was indeed serious about liquidating its portfolio. Further they candidly reminded me how valuing the portfolio conservatively made the tax consequences of converting to a liquidating trust more favorable for investors(the management group was also a large shareholder).

I did a lot of unconventional work, but didn’t mindlessly dig for more info. It wasn’t a huge position but since its going to be locked up in a non transferable liquidiating trust, and it was an idea most people thought too ugly, a bit of extra work was justified.

The company already paid back most of my initial investment after selling one investment and the portfolio still has a lot of value. The true test will be in the final IRR when its all said and done.

See also: The hard thing about finding easy things

Riches Among the Ruins

No Economy is too small, no political crisis is too dire, and no country is too bankrupt for a solo operator like me to find riches among the ruins.

-Robert Smith

Riches Among the Ruins: Adventures in the Dark Corners of the Global Economy is an incredibly entertaining bottom up look at frontier market crises over the last 3 decades from the perspective of a travelling distressed debt trader. Each chapter is dedicated to Robert Smith’s experience in a particular country: El Salvador, Turkey, Russia, Nigeria, Iraq, etc, etc. Each country is unique, but Smith’s weaves several key lessons throughout his memoir.

Anyone who seeks profits in inefficient markets could benefit from Smith’s experience.

Information vacuums are key for middleman and arbitrageurs

In the mid 1980s no one had any idea what an El Salvador bond was worth- which is to say, they had no idea what value others might attach to it. The ignorance, this information vacuum, was my bliss. The seller’s price was simply a measure of how desperately he wanted to dispose of a paper promise of the government of El Salvador, and the buyer’s measure of how eager he was to convert his local currency into a glimmer of hope and seeing dollars down the road. The spread, my profit, was the difference between the two. In a fledgling market, with no reporting mechanisms and precious little information floating around, the spread can be enormous, and there was no regulatory or legal restrictions on how much you could make on a transaction.

Though my sellers and buyers, usually the representative of foreign companies doing business in El Salvador, often knew each other , played golf together, or broke bread together at American Chamber of Commerce breakfasts, I knew it would take some time before they eventually started to compare notes. At the beginning I doubt any of them even mentioned they were trying to sell or buy El Salvador bonds because the market didn’t exist yet. But until the market matured it was a gold rush, and I developed a monopoly on that most precious of all commodities in any market: information. I found out who wanted to sell, who wanted to buy and their price, and I held that information very tight to the vest.

In some cases buyers and sellers were on different floors in the same office building, or different divisions of the same global corporation. The biggest challenges for foreign companies doing business in the developing world was converting local currency revenues back into dollars. One way to get money out was to buy dollar bonds at fixed exchange rate and over time collect principal and interest in dollars.

Creativity and information edge: Struggles over bondholder lists

In almost every country, Smith, goes through difficulty to get the list of people holding the bonds in which he was seeking to make a market. Arbitrageurs and brokers who had access to the list guarded it aggressively, because it gave them an edge in acquiring positions at a discount, or profiting as a middleman. This was a key bit of information, available from connections at the Central Bank or other places.

Discounted Venture Capital

I posted on Seeking Alpha about my investment in Crossroads Capital (XRDC), a busted venture capital BDC trading at ~60% of book value, with 70% of market cap in cash. It has a messy portfolio, but not a lot needs to go right for signficant upside. For those with the means and/or the investment mandate, getting an NDA and buying the individual portfolio companies from XRDC might be the better option. Crossroads Capital hired Setter Capital to market its holdings. Setter Capital specializes in the fascinating private equity secondary market.

Here are a few residual thoughts on deep value investing in the busted BDC/private equity/venture capital space.

There is a bit of irony in a deep value liquidation play with assets that consist of preferred shares in growth oriented venture capital investments. Venture capitalists bet big on change, while value investors generally focus on mean reversion, yet as Marc Andreessen pointed out, there are actually similarities between the philosophies underpinning value investing and venture capital. Both styles of investing emphasize fundamental analysis, long term thinking, and ignoring market noise, while taking advantage of some sort of mispricing.

However, a lot of venture capital investments are preferred equity with quite favorable liquidation preferences. The prospective buyer will conduct due diligence on the operations of the business, and the rights of the particular security. With an investment in XRDC one can determine the aggregate valuation paid by an outside investor(about 3x EBITDA after subtracting out all the excess cash in the BDC), and can compare valuations with other BDCs holding the same security (top holding is marked over 20% higher by another BDC), but there is limited public information on each individual security. Based on research of public sources, several of the portfolio companies appear to be doing pretty well, but a couple are also in trouble. My working hypothesis is that the absurdly large discount creates a “heads I win, tails I don’t lose that much” scenario. However, cherry picking the best companies out of XRDC’s portfolio and buying them directly would be even better.

I look forward to more opportunities like this.