Tagged: Strategy

Empty Spaces on Maps

Prior to the 15th century, maps generally contained no empty spaces. Mapmakers simply left out unfamiliar areas, or filled them with imaginary monsters and wonders. This practice changed in Europe as the great age of exploration began. In Sapiens, Yuval Harari argues that leaving empty spaces on maps reflected a more scientific mindset, and was a key reason that Europeans were able to conquer and colonize other continents, in spite of starting with a technological and military disadvantage. Conquerors were curious, but the conquered were uninterested in the unknown. Amerigo Vespucci, after whom our home continent was named, was a strong advocate of leaving unknown spaces on maps blank. Explorers used these maps to move beyond the known, sailing into those empty spaces so they did not stay unmapped for long.

The same phenomenon occurs in business. In the Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Christensen shows why large established ostensibly well-run companies so frequently miss out on major waves of innovation. A key principle in the book is the difference between sustaining technologies, which merely improve the status quo, and disruptive technologies, which offer a new and unique value proposition. Large companies will frequently focus on sustaining technologies, and ignore disruptive technologies that serve fringe markets initially. Ultimately its disruptive technologies that define business history. Yet complacent companies don’t figure that out until its too late.

Companies whose investment processes demand quantification of market sizes and financial returns before they can enter a market get paralyzed or make serious mistakes when faced with disruptive technologies.

There are two parts to overcoming the innovator’s dilemma:

- Acknowledging that the market sizes and potential financial returns of a nascent market are unknowable and cannot be quantified (drawing the blank spaces on the maps) and;

- Entering the nascent market in the absence of quantifiable data- (travelling into the empty space)

Analogous ideas also apply to investing. In Investing in the Unknown and Unknowable, Richard Zeckhauser distinguishes between situations where the probability of future states is known, and when it is not. The former is the realm of academic finance and decision theory. The latter is the real world.

The real world of investing often ratchets the level of non-knowledge into still another dimension, where even the identity and nature of possible future states are not known. This is the world of ignorance. In it, there is no way that one can sensibly assign probabilities to the unknown states of the world. Just as traditional finance theory hits the wall when it encounters uncertainty, modern decision theory hits the wall when addressing the world of ignorance.

Human bias leads us into classic decision traps when confronted with the unknown and unknowable. Overconfidence and recollection bias are especially pernicious. Yet just because we are ignorant doesn’t mean we need to be nihilists. The essay has some key optimistic conclusions:

The first positive conclusion is that unknowable situations have been and will be associated with remarkably powerful investment returns. The second positive conclusion is that there are systematic ways to think about unknowable situations. If these ways are followed, they can provide a path to extraordinary expected investment returns. To be sure, some substantial losses are inevitable, and some will be blameworthy after the fact. But the net expected results, even after allowing for risk aversion, will be strongly positive.

Examples in the essay include David Ricardo buying British Sovereign bonds on the eve Battle of Waterloo, venture capital, frontier markets with high political risk, and some of Warren Buffet’s more non-standard insurance deals. Yet since even the industries that seem simple and steady can be disrupted, its critical to keep these ideas in mind at all times in order to avoid value traps.

The best returns are available to those willing to acknowledge ignorance, then systematically venture into blank spaces on maps and in markets.

Investing in the Unknown and Unknowable

See also:

A Different Kind of Death Spiral: ETFS, Mutual Funds and Systemic Risk

The rapid growth of ETFs is one of the most significant changes to financial markets in the last decade. Total ETF AUM grew from $0.5 trillion in 2008 to over $3 trillion by the end of 2017. More remarkably, AUM of ETFs invested in illiquid sectors such as global bank loan , emerging market bonds, and global high yield bonds increased 14 fold from $10 billion 2007 to $140 billion at the end of 2017. Prior to the last financial crisis, ETFs were a relatively small niche, but these past few years it seems like every asset manager has launched an ETF. Most investors have a large portion of their retirement assets in ETFs, and many investors exclusively invest in ETFs.

This is a major systemic change from what was in place prior to the last financial crisis. Since markets go through cycles its worth asking: how will the ETF ecosystem hold up next time there is market turmoil?

ETFs have overall been a massive benefit to investors because they lowered costs. Yet as more and investors put more and more money into ETFs, there are growing signs of distortions. Some investors have pointed out how ETFs are creating bizarre valuations that are unlikely to be sustainable. Additionally, there are growing signs that the ETF structure is far more fragile than most market participants realize. These aren’t just doom and gloom conspiracies from Zero Hedge. Organizations such as the IMF, DTCC, G20 Financial Stability Board, and the Congressional Research Service have all pointed out possible risks from the unintended consequences of ETF growth.

How the ETF ecosystem works

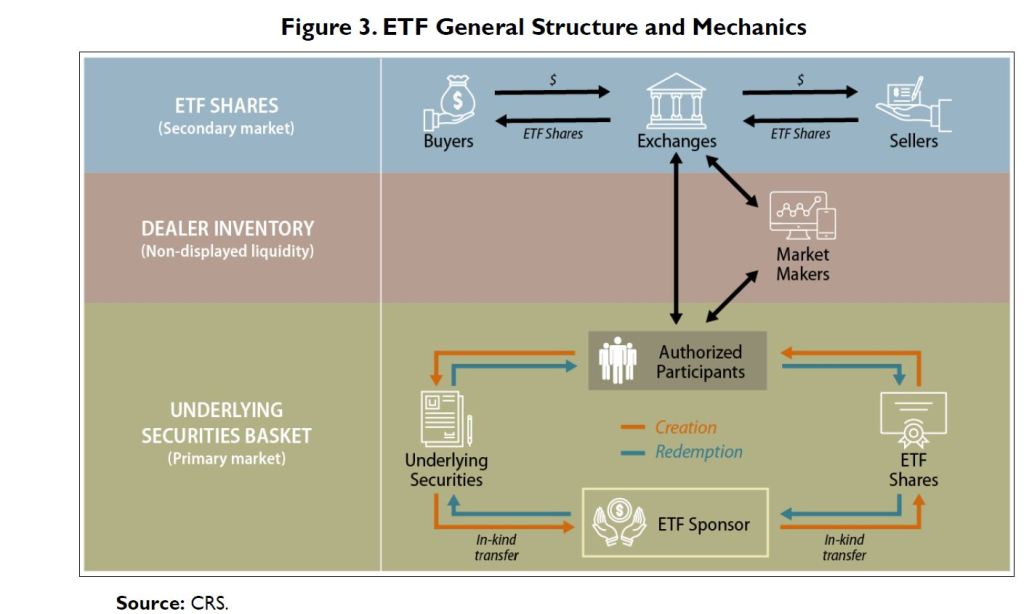

The structure and mechanics of ETFs are unique and different from mutual funds. Unlike mutual funds, ETFs generally don’t have to meet redemptions in cash. The key difference is the role of Authorized Participants (APs), and the arbitrage mechanism. The Congressional Research Service provides a handy diagram explaining the structure (Most fund sponsors have similar diagrams in their whitepapers) :

From the same CRS paper:

In a typical ETF creation process, the ETF sponsor would first publish a list of securities in an ETF share basket. The APs have the option to assemble and deliver the securities basket to the ETF sponsor. Once the sponsor receives the basket of securities, it would deliver new ETF shares to the AP. The AP could then sell the ETF shares on a stock exchange to all investors. The redemption process is in reverse, with the APs transferring ETF shares to sponsors and receiving securities.

ETF shares are created and redeemed by authorized participants in the primary market. The fund sponsors do not sell their ETF shares directly to investors; instead, they issue the shares to APs in large blocks called “creation units” that usually consist of 50,000 or more shares. The APs’ creation and redemption process often involves the purchase of the created units “in-kind” rather than in cash. This means that the shares are exchanged for a basket of securities instead of cash settlements.

The supply of ETF shares is flexible, meaning that the shares can be created or redeemed to offset changes in demand; however, only authorized participants can create or redeem ETF shares from the sponsors. A large ETF may have dozens of APs, whereas smaller ETFs could use fewer of them.

The “arbitrage mechanism” is a key feature of the ETF ecoystem. The market incentivizes APs to correct supply demand imbalances for ETFs because they can always exchange underlying shares for the securities in the portfolio and vice versa. So theoretically ETFs should not end up with discounts or premiums to NAVs like closed end funds.

Additionally, since the ETF Sponsor can redeem in kind, rather than in cash, they don’t need to sell underlying securities to meet redemption requests, like with mutual funds. Additionally, unlike with mutual funds, you get some intraday price transparency. Sometimes media commentary on “illiquid assets in liquid wrappers” mixes these up, but the nuance is important to how the respective ecosystems will react to market turmoil.

The arbitrage mechanism is a huge benefit for ETFs, and it works pretty well for deep liquid markets, like large cap stocks. Yet with less liquid assets such as leveraged loans or high yield bonds, there is reason to worry. ETFs haven’t really solved the liquidity mismatch problem. Closely related, any understanding of market history leads us to conclude that APs are unlikely to function in a falling market.

Liquidity mismatch in ETFs

Theoretically if there is a flood of selling at ETF level, APs can buy from portfolio managers, then exchange for underlying securities. However what happens if there is no bid/ask for some or all of the underlying securities?

There are several large ETFs that consist of leveraged loans and high yield bonds. A retail investor can have instant liquidity in the ETF market, and theoretically if there is an imbalance in the secondary market APs will step in and exchange ETF shares for the underlying bonds and loans. Yet these underlying assets can go days without actually trading(they are “trade by appointment”) . ETFs may be a small percentage of all outstanding bonds/loans, yet there is very little turnover of these assets, and often its difficult to get pricing. Its not clear how the market would respond if there was a macro event that caused loan prices to gap down, and investors to seek redemptions from ETFs en masse. Prior to the last financial crisis, few ETFs held high yield bonds, and no ETFs held leveraged loans.

According to the DTCC:

Some analysts assert that ETFs have become so large in certain markets that the underlying securities may no longer be sufficiently liquid to facilitate ETF creation/redemption activity during periods of stress and could result in price dislocations.

From Duke Law’s FinReg Blog:

Consider a crisis scenario where selling pressure causes underlying assets (like fixed income securities) to become illiquid and rapidly lose value prompting ETF holders to quickly sell their shares. Here market makers and APs would likely widen their bid-ask spreads to “compensate for market volatility and pricing errors.” Increased fund redemptions in the primary market could also detrimentally change the composition of the underlying portfolio basket causing APs – who no longer want to redeem ETF shares and receive, in-kind, the plummeting and illiquid securities – to withdraw from the market altogether.

Also notable, post financial crisis regulatory changes caused bond dealers to hold less inventory. This can mean less liquidity in a crisis, as this recent academic paper notes:

When an extreme crisis hits, historically, OTC market liquidity disappears. That is, no one is available to take the other side of the trade. There are simply no bids, no offers, and no trading activity in OTC markets. The recent reduction in dealer inventories means that markets will be even more volatile in the next crisis.

This is unlikely to be a problem for deep liquid markets such as large cap stocks. So any problem with popular stock index funds is likely to be resolve itself quickly But it could take a long time to unwind problems in leveraged loan and high yield bond ETFs.

Won’t the APs fix this?

Its important to emphasize that the APs have no fiduciary duty to provide liquidity. The AP will have an agreement with the fund sponsor, but the fund sponsor does not compensate the AP directly. APs can profit by acting as dealers in the secondary market, or clearing brokers, thus collecting payment for processing and creation/redemption of ETF shares from a wide variety of market participants. APs can stop providing liquidity anytime they want. In the event of a crisis it may be prudent to do so. From Duke Law:

As such, a reliance on discretionary liquidity, in the context of a crisis is inherently “fragile” since dealers and market makers will stop providing it once they start incurring losses, or their balance sheets are negatively impacted from other exposures and they can no longer bear the additional risk from providing the liquidity support

In 2013 some ETFs traded at a steep discount when Citigroup hit its internal risk limits. That was in the middle of a great bull market. What will happen if there is a serious macro problem? As a historical precedent, during the financial crisis the auction rate security market collapsed when discretionary liquidity providers exited due to turmoil.

A different kind of death spiral

There are risks for both ETFs and Mutual Funds that hold illiquid assets. However the reasons are different, and the nuances of a blow up will be different.

A mutual fund can get exemptive relief from the SEC to suspend cash redemptions in extreme circumstances. Mutual fund investors, who thought they had a daily liquidity vehicle, are left holding an illiquid asset. This happened to the Third Avenue Focused Credit fund a couple years back. This caused a short lived mini-panic in the high yield debt market. When the fund suspended cash redemptions, they paid redemptions in shares of a liquidating trust. An outside party offered to buy the shares at a 61% discount to the NAV, which had already declined sharply.

In the case of an ETF it’s a bit more complicated. The death spiral could simply take the form of a self reinforcing feedback loop. Retail investors would be able to exit, albeit at a steep discount. APs would sell underlying securities that they can sell, causing prices to plummet, causing further retail panic. Some assets are more illiquid than others, and once once the dust settles, the ETF will be left holding the most illiquid and opaque assets.

During the past few years we’ve seen a few tremors. There was the short incident in 2013 mentioned above. In May 2010 and August 2015 there were large one day price swings in more liquid parts of the ETF market probably caused by algorithms. In February 2018 there was the great VIX blowup/ “volmageddon”. The VIX example was a bit different because it involved very unique derivatives, but I think the bigger more interesting problems could be in the credit space. In 2018Q4 there was some volatility in the credit space, and MSCI noted ETFs appeared to have a mild impact on bid/ask spreads. Yet by historical standards what happened in 2018Q4 was very minor.

These examples all occurred during a long bull market. What will happen in the next 2008 type scenario? I Still need to look more into how they might actually unwind.

So what can an investor do?

Most ETFs(and mutual funds) will probably be fine. During a crisis there might be temporary NAV discounts even for large cap index funds and lots of panic selling all around. Mutual fund investors will redeem at the worst possible time, and funds will sell shares into a falling market to meet these requests. Headlines will be full of doom and gloom. The prudent thing for most investors will be to ignore it all. Continue dollar cost averaging across the decades to retirement and beyond.

Nonetheless, investors holding some of the more esoteric, illiquid ETFs and mutual funds could be in for an unpleasant surprise and possible permanent capital impairment. Even though these potentially problematic funds are a small portion of the overall market, there is likely to be systemic contagion, as the IMF noted.

I’ve purchased some cheap puts on more fragile ETFs(mainly high yield bond and leveraged loan) although the lack of an imminent catalyst means that the position size needs to be small. I’ll be looking more closely at the way these different types of structures are unwound, since there are likely to be some major time sensitive opportunities next time it occurs.

Other possible case studies of the unwinding of illiquid assets in liquid wrappers:

- UK open end commercial property funds during Brexit vote

- Auction rate securities during financial crisis

- Interval Funds during the financial crisis.

- Other mutual fund redemption suspensions and ETF tremors?

See also:

Antifragile Morning Routine

The idea of having “morning routine” is a favorite topic on the interwebs these days. Its now at the point where I can barely tell apart parody from serious articles. I think Tim Ferriss started it all by asking every single one of his guests their morning routine. Most people couldn’t resist listening. I know I couldn’t.

When a “high performer” provides a detail on their morning routine, they are merely providing an example of a thing that works for a very specific set of circumstances. Nothing more nothing less. Just because it worked for them, doesn’t mean it will work for you.

Nonetheless it is still a useful data point. Weird low cost ideas are usually worth trying.

Eliminating decision fatigue

I view morning routines as constrained optimization problem that will have different solutions for different people. It might even have different answers on different days for the same person.

I’m generally skeptical of anything overly complicated. The key benefit of a morning routine is it reduces decision fatigue. The morning routine is a “default setting” . But if one is obsessed with following it, it becomes a burden and prevents serendipity.

Towards an antifragile morning routine

The ability to adapt to changing circumstances is more important than having a set routine. Some days you have to work late. Other days you may have an early meeting. Or maybe your child gets sick. What if your spouse or mistress needs your support? What do you do when you travel or are awoken by a phone call? What then?

It doesn’t make sense to rigidly expect the world to conform to your plan. A fragile morning routine is worse than no morning routine. A robust morning routine is better. An antifragile morning routine is best.

Personally I have a “default setting” to do when I’m home and nothing special is happening. I have a handful of different algorithms I can enact depending on other circumstances that come up. This gives me the comfort of a routine without rigidity. If I’m travelling I’ll usually explore the local area just a bit.

Sometimes an emergency leads to a new insight.

Why its wise to think in bets

The secret is to make peace with walking around in a world where we recognize that we are not sure and that’s okay. As we learn more about how our brains operate, we recognize that we don’t perceive the world objectively. But our goal should be to try.

Annie duke’s “Thinking in Bets” is basically long essay with an extremely valuable message. Under a plethora of entertaining anecdotes about professional poker it contains a valuable framework for making decisions in this uncertain world. This requires accepting uncertainty, and being intellectually honest. Good decision making habits compound over time

Thinking in Bets is a slightly less nerdy and less nuanced compliment to pair with “Fortune’s Formula”. It also fits in well with some of the more important behavioral finance books, such as…. Misbehaving, and Hour Between wolf and dog, Kluge, etc.

I’ve organized some of my highlights and notes from Thinking in Bets below.

The implications of treating decisions as bets made it possible for me to find learning opportunities in uncertain environments. Treating decisions as bets, I discovered, helped me avoid common decision traps, learn from results in a more rational way, and keep emotions out of the process as much as possible.

Outcome quality vs decision quality

We can get better at separating outcome quality from decision quality, discover the power of saying, “I’m not sure,” learn strategies to map out the future, become less reactive decision-makers, build and sustain pods of fellow truthseekers to improve our decision process, and recruit our past and future selves to make fewer emotional decisions. I didn’t become an always-rational, emotion-free decision-maker from thinking in bets. I still made (and make) plenty of mistakes. Mistakes, emotions, losing—those things are all inevitable because we are human. The approach of thinking in bets moved me toward objectivity, accuracy, and open-mindedness. That movement compounds over time

Thinking in bets starts with recognizing that there are exactly two things that determine how our lives turn out: the quality of our decisions and luck. Learning to recognize the difference between the two is what thinking in bets is all about.

Why are we so bad at separating luck and skill? Why are we so uncomfortable knowing that results can be beyond our control? Why do we create such a strong connection between results and the quality of the decisions preceding them? How

Certainty is an illusion

Trying to force certainty onto an uncertain world is a recipe for poor decision making. To improve decision making, learn to accept uncertainty. You can always revise beliefs.

Seeking certainty helped keep us alive all this time, but it can wreak havoc on our decisions in an uncertain world. When we work backward from results to figure out why those things happened, we are susceptible to a variety of cognitive traps, like assuming causation when there is only a correlation, or cherry-picking data to confirm the narrative we prefer. We will pound a lot of square pegs into round holes to maintain the illusion of a tight relationship between our outcomes and our decisions.

There are many reasons why wrapping our arms around uncertainty and giving it a big hug will help us become better decision-makers. Here are two of them. First, “I’m not sure” is simply a more accurate representation of the world. Second, and related, when we accept that we can’t be sure, we are less likely to fall

Our lives are too short to collect enough data from our own experience to make it easy to dig down into decision quality from the small set of results we experience.

Incorporating uncertainty into the way we think about our beliefs comes with many benefits. By expressing our level of confidence in what we believe, we are shifting our approach to how we view the world. Acknowledging uncertainty is the first step in measuring and narrowing it. Incorporating uncertainty in the way we think about what we believe creates open-mindedness, moving us closer to a more objective stance toward information that disagrees with us. We are less likely to succumb to motivated reasoning since it feels better to make small adjustments in degrees of certainty instead of having to grossly downgrade from “right” to “wrong.” When confronted with new evidence, it is a very different narrative to say, “I was 58% but now I’m 46%.” That doesn’t feel nearly as bad as “I thought I was right but now I’m wrong.” Our narrative of being a knowledgeable, educated, intelligent person who holds quality opinions isn’t compromised when we use new information to calibrate our beliefs, compared with having to make a full-on reversal. This shifts us away from treating information that disagrees with us as a threat, as something we have to defend against, making us better able to truthseek. When we work toward belief calibration, we become less judgmental .

In an uncertain world, the key to improving is to revise, revise, revise.

Not much is ever certain. Samuel Arbesman’s The Half-Life of Facts is a great read about how practically every fact we’ve ever known has been subject to revision or reversal. We are in a perpetual state of learning, and that can make any prior fact obsolete. One of many examples he provides is about the extinction of the coelacanth, a fish from the Late Cretaceous period. A mass-extinction event (such as a large meteor striking the Earth, a series of volcanic eruptions, or a permanent climate shift) ended the Cretaceous period. That was the end of dinosaurs, coelacanths, and a lot of other species. In the late 1930s and independently in the mid-1950s, however, coelacanths were found alive and well. A species becoming “unextinct” is pretty common. Arbesman cites the work of a pair of biologists at the University of Queensland who made a list of all 187 species of mammals declared extinct in the last five hundred years.

Getting comfortable with this realignment, and all the good things that follow, starts with recognizing that you’ve been betting all along.

The danger of being too smart

The popular wisdom is that the smarter you are, the less susceptible you are to fake news or disinformation. After all, smart people are more likely to analyze and effectively evaluate where information is coming from, right? Part of being “smart” is being good at processing information, parsing the quality of an argument and the credibility of the source. So, intuitively, it feels like smart people should have the ability to spot motivated reasoning coming and should have more intellectual resources to fight it. Surprisingly, being smart can actually make bias worse. Let me give you a different intuitive frame: the smarter you are, the better you are at constructing a narrative .

… the more numerate people (whether pro- or anti-gun) made more mistakes interpreting the data on the emotionally charged topic than the less numerate subjects sharing those same beliefs. “This pattern of polarization . . . does not abate among high-Numeracy subjects.

It turns out the better you are with numbers, the better you are at spinning those numbers to conform to and support your beliefs. Unfortunately, this is just the way evolution built us. We are wired to protect our beliefs even when our goal is to truthseek. This is one of those instances where being smart and aware of our capacity for irrationality alone doesn’t help us refrain from biased reasoning. As with visual illusions, we can’t make our minds work differently than they do no matter how smart we are. Just as we can’t unsee an illusion, intellect or willpower alone can’t make us resist motivated reasoning.

The Learning Loop

Thinking rationally is a lot about revising, and refuting beliefs(link to reflexivity) By going through a learning loop faster we are able to get an advantage. This is similar to John Boyd’s concept of an OODA loop.

We have the opportunity to learn from the way the future unfolds to improve our beliefs and decisions going forward. The more evidence we get from experience, the less uncertainty we have about our beliefs and choices. Actively using outcomes to examine our beliefs and bets closes the feedback loop, reducing uncertainty. This is the heavy lifting of how we learn.

Chalk up an outcome to skill, and we take credit for the result. Chalk up an outcome to luck, and it wasn’t in our control. For any outcome, we are faced with this initial sorting decision. That decision is a bet on whether the outcome belongs in the “luck” bucket or the “skill” bucket. This is where Nick the Greek went wrong. We can update the learning loop to represent this like so: Think about this like we are an outfielder catching a fly ball with runners on base. Fielders have to make in-the-moment game decisions about where to throw the ball.

Key message: How poker players adjust their play from experience determines how much they succeed. This applies ot any competitive endeavor in an uncertain world.

Intellectual Honesty

The best players analyze their performance with extreme intellectual honesty. This means if they win, they may end up being more focused on erros they made, as told in this anecdote:

In 2004, my brother provided televised final-table commentary for a tournament in which Phil Ivey smoked a star-studded final table. After his win, the two of them went to a restaurant for dinner, during which Ivey deconstructed every potential playing error he thought he might have made on the way to victory, asking my brother’s opinion about each strategic decision. A more run-of-the-mill player might have spent the time talking about how great they played, relishing the victory. Not Ivey. For him, the opportunity to learn from his mistakes was much more important than treating that dinner as a self-satisfying celebration. He earned a half-million dollars and won a lengthy poker tournament over world-class competition, but all he wanted to do was discuss with a fellow pro where he might have made better decisions. I heard an identical story secondhand about Ivey at another otherwise celebratory dinner following one of his now ten World Series of Poker victories. Again, from what I understand, he spent the evening discussing in intricate detail with some other pros the points in hands where he could have made better decisions. Phil Ivey, clearly, has different habits than most poker players—and most people in any endeavor—in how he fields his outcomes. Habits operate in a neurological loop consisting of three parts: the cue, the routine, and the reward. A habit could involve eating cookies: the cue might be hunger, the routine going to the pantry and grabbing a cookie, and the reward a sugar high. Or, in poker, the cue might be winning a hand, the routine taking credit for it, the reward a boost to our ego. Charles Duhigg, in The Power of Habit, offers the golden rule of habit change….

Being in an environment where the challenge of a bet is always looming works to reduce motivated reasoning. Such an environment changes the frame through which we view disconfirming information, reinforcing the frame change that our truthseeking group rewards. Evidence that might contradict a belief we hold is no longer viewed through as hurtful a frame. Rather, it is viewed as helpful because it can improve our chances of making a better bet. And winning a bet triggers a reinforcing positive update.

Note: Intellectual Honesty thinking clearly= thinking in bets

Good decisions compound

One useful model is to view everything as one big long poker game. Therefore the result of individual games won’t upset you so much. Furthermore, good decision making habits compound over time. So the key is to always be developing good long term habits, even as you deal with the challenges of a specific game.

The best poker players develop practical ways to incorporate their long-term strategic goals into their in-the-moment decisions. The rest of this chapter is devoted to many of these strategies designed to recruit past- and future-us to help with all the execution decisions we have to make to reach our long-term goals. As with all the strategies in this book, we must recognize that no strategy can turn us into perfectly rational actors. In addition, we can make the best possible decisions and still not get the result we want. Improving decision quality is about increasing our chances of good outcomes, not guaranteeing them. Even when that effort makes a small difference—more rational thinking and fewer emotional decisions, translated into an increased probability of better outcomes—it can have a significant impact on how our lives turn out. Good results compound. Good processes become habits, and make possible future calibration and improvement.

At the very beginning of my poker career, I heard an aphorism from some of the legends of the profession: “It’s all just one long poker game.” That aphorism is a reminder to take the long view, especially when something big happened in the last half hour, or the previous hand—or when we get a flat tire. Once we learn specific ways to recruit past and future versions of us to remind ourselves of this, we can keep the most recent upticks and downticks in their proper perspective. When we take the long view, we’re going to think in a more rational way.

Life, like poker, is one long game, and there are going to be a lot of losses, even after making the best possible bets. We are going to do better, and be happier, if we start by recognizing that we’ll never be sure of the future. That changes our task from trying to be right every time, an impossible job, to navigating our way through the uncertainty by calibrating our beliefs to move toward, little by little, a more accurate and objective representation of the world. With strategic foresight and perspective, that’s manageable work. If we keep learning and calibrating, we might even get good at it.

Hierarchies vs networks: Notes on the Square and the Tower

“Often the biggest changes in history are the achievements of thinly documented, informally organized groups of people. “

The Square and the Tower examines the role informal networks have played throughout history. Its one of the few books I’ve seen that takes a rigorous, empirical and non-sensational look at what secret societies actually did throughout history. More importantly it delineates between societies/institutions that are driven by informal networks, vs those that are driven by formal hierarchies. The world kind of goes back and forth between the two over time. The spread of diseases and ideas follow similar processes and are both are heavily influenced by the role of networks and hierarchies in society. Among its most useful(and amusing) conclusions is that Martin Luther and Donald Trump have something very important in common.

Historical Background

The first ‘networked era’ followed the introduction of the printing press to Europe in the late fifteenth century and lasted until the end of the eighteenth century. The second – our own time – dates from the 1970s, though I argue that the technological revolution we associate with Silicon Valley was more a consequence than a cause of a crisis of hierarchical institutions. The intervening period, from the late 1790s until the late 1960s, saw the opposite trend: hierarchical institutions re-established their control and successfully shut down or co-opted networks. The zenith of hierarchically organized power was in fact the mid-twentieth century – the era of totalitarian regimes and total war.

Martin Luther and Donald Trump

The key insight is that Martin Luther and Donald Trump and their respective suorters both made highly skilld and aggressive use of a new communication medium to spread their message. Luther had ht ebrand new thing called the printing press. Trump had this brand new thing called social media(mainly twitter)

Without Gutenberg, Luther might well have become just another heretic whom the Church burned at the stake, like Jan Hus. His original ninety-five theses, primarily a critique of corrupt practices such as the sale of indulgences, were originally sent as a letter to the Archbishop of Mainz on 31 October 1517. It is not wholly clear if Luther also nailed a copy of them to the door of All Saints’ Church, Wittenberg, but it scarcely matters. That mode of publishing had been superseded. Within months, versions of the original Latin text had been printed in Basel, Leipzig and Nuremberg. By the time Luther was officially condemned as a heretic by the Edict of Worms in 1521, his writings were all over German-speaking Europe. Working with the artist Lucas Cranach and the goldsmith Christian Döring, Luther revolutionized not only Western Christianity but also communication itself. In the sixteenth century German printers produced almost 5,000 editions of Luther’s works, to which can be added a further 3,000 if one includes other projects he was involved with, such as the Luther Bible. Of these 4,790 editions, almost 80 per cent were in German, as opposed to Latin, the international language of the clerical elite.3 Printing was crucial to the Reformation’s success. Cities with at least one printing press in 1500 were significantly more likely to adopt Protestantism than cities without printing, but it was cities with multiple competing

Likewise, Trump was able to get an enormous amount of massive publicity do to his exploitation of social media. It also didn’t hurt that their were highly skilled foreign actors also using social media to spread his influence. Much of this was done in an automated fashion, using bots, etc. Social media allowed this message to spread directly without any filter from media gatekeepers.

Gutenberg’s printing press helped make Lutheranism. Twitter bots helped make Trumpism.

Difficult to suppress

Why was Protestantism so resistant to repression? One answer to that question is that, as they proliferated throughout northern Europe, the Protestant sects developed impressively resilient network structures.

Similarly, traditional political operatives have had difficulty penetrating the social media networks that Trump has so successfully exploited.

Bringing the medium to the masses

Just as the printing press caused a drastic fall in the price of written books, the falling prices of phones and PCs made the internet more widely accessible.

The decline in the price of a PC between 1977 and 2004 followed a very similar trajectory to the decline in the price of a book between the 1490s and the 1630s. Yet the earlier, slower revolution in information technology appears to have had the larger economic impact. The best explanation for this difference is the role of printing in disseminating hitherto unavailable knowledge fundamental to the functioning of a modern economy. The first known printed mathematics text was the Treviso Arithmetic (1478). In 1494, Luca Pacioli’s Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita was published in Venice, extolling the benefits of double-entry book-keeping.

Luther and Trump both spread their message just as new technology was making it much easier for something to go viral. Luther upended the church hierarchy by bringing religious texts and thoughts to the common people. Prior to Luther religious text were almost exclusively in Latin, which the common people could not read or understand. The idea that common people could be allowed to read the bible was considered heretical (see a world lit only by fire). Luther spread his messages into far away villages causing the Catholic church to lose control of its traditional followers. Likewise, Trump upended the political hierarchy by spreading a populist message far and wide, even overtaking previously Democratic strongholds. Many people who felt abandoned by the political process went to his rallies. Washington insiders have been thrown out, an outsiders have taken control. Many readers of this blog may not want to think of Trump in this way, but the analogy is valuable in understanding why Trump has been so successful.

Spread of disease

The speed with which an infectious disease spreads has as much to do with the network structure of the exposed population as with the virulence of the disease itself, as an epidemic amongst teenagers in Rockdale County, Georgia, made clear twenty years ago. The existence of a few highly connected hubs causes the spread of the disease to increase exponentially after an initial phase of slow growth.7 Put differently, if the ‘basic reproduction number’ (how many other people are newly infected by a typical infected individual) is above one, then a disease becomes endemic;

Impact on economics

For economists, too, advances in network science had important implications. Standard economics had imagined more or less undifferentiated markets populated by individual utility-maximizing agents with perfect information. The problem – resolved by the English economist Ronald Coase, who explained the importance of transaction costs* – was to explain why firms existed at all. (We are not all longshoremen, hired and paid by the day like Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront, because employing us regularly within firms can reduce the costs that arise when workers are hired on a daily basis.) But if markets were networks, with most people inhabiting more or less interconnected clusters, the economic world looked very different, not least because information flows were determined by the networks’ structures. Many exchanges are not just one-off transactions in which price is a matter of supply and demand. Credit is a function of trust, which in turn is higher within a cluster of similar people (e.g. an immigrant community). This has implications not only for employment markets, the case studied by Granovetter. Closed networks of sellers can collude against the public and deter innovation. More open networks can promote innovation as new ideas reach the cluster thanks to the strength of weak ties. Such observations prompted the question of

Spread of ideas

The key point, as with disease epidemics, is that network structure can be as important as the idea itself in determining the speed and extent of diffusion. In the process of going viral, a key role is played by nodes that are not merely hubs or brokers but ‘gate-keepers’ – people who decide whether or not to pass information to their part of the network. Their decision will be based partly on how they think that information will reflect back on them. Acceptance of an idea, in turn, can require it to be transmitted by more than one or two sources. A complex cultural contagion, unlike a simple disease epidemic, first needs to attain a critical mass of early adopters with high degree centrality (relatively large numbers of influential friends).In the words of Duncan Watts, the key to assessing the likelihood of a contagion-like cascade is ‘to focus not on the stimulus itself but on the structure of the network the stimulus hits’. This helps explain why, for every idea that goes viral, there are countless others that fizzle out in obscurity because they began with the wrong node, cluster or network.

…

That is because so many real-world networks follow Pareto-like distributions: that is, they have more nodes with a very large number of edges and more nodes with very few than would be the case in a random network. This is a version of what the sociologist Robert K. Merton called ‘the Matthew effect’, after the Gospel of St Matthew: ‘For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath.’* In science, success breeds success: to him who already has prizes, more prizes shall be given. Something similar can be seen in ‘the economics of superstars’. In the same way, as many large networks

Just like the printing press destroyed the ruling classes monopoly on spirituality, social media has destroyed the “establishment’s” monopoly on political ideology.

Martin Luther and Donald Trump would agree on this

The value of improvisation and informal processes

Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed summarizes the key dangers of centrally managed social engineering projects. Its a bit dense, but well worth it. It shows similarities between many seemingly different disasters caused by top-down control and central planning. Case studies include modernist architecture, Soviet collectivization, herding or rural people into villages in Africa,and early errors in scientific agriculture, etc.

Anyone trying to build and manage an organization needs to be aware of the lessons in this book.

One key lesson is that practical knowledge, informal processes, and improvisation in the face of unpredictability are indispensable.

Formal scheme was parasitic on informal processes that alone, it could not create or maintain. The the degree that the formal scheme made no allowance for those processes or actually suppressed them, it failed both its intended beneficiaries and ultimately its designers as well. “

Radically simplified designs for social organization seem to court the same risks of failure courted by radically simplified designs for natural environments.

It makes the case for resilience of both social and natural diversity, and a strong case for limits about what can be known about complex social order. Avoid reductive social science.

Four elements of centrally planned disasters

According to the book, there four elements necessary for a full fledged disaster to be caused by state initiated social engineering.

- Administrative ordering of nature and society

- “High Modernist Ideology” a faith that borrowed the legitimacy of science and technology. Uncritical unskeptical public and therefore unscientific optimism about possibilities for comprehensive planning of human settlement and production. Often with aesthetic terms too.

- Authoritarian state willing to use the full weight of its coercive power for #2

- Prostrate civil society lacking capacity to resist these plans.

“By themselves they are unremarkable tools of modern statecraft; they are as vital to the maintenance of our welfare and freedom as they are to the designs of a would be modern despot. They undergird the concept of citizenship and the provision of social welfare just as they might undergird a policy of rounding up undesirable minorities.”

Overlooking ecology

The discussion of the ecological disasters caused by forestry regulation in 18th and 19th century Germany is instructive:

The metaphorical value of this brief account of scientific production forestry is that it illustrates the dangers of dismembering an exceptionally complex and poorly understood set of relations and processes in order to isolate a single element of instrumental value. The instrument, the knife, that carved out the new, rudimentary forest was the razor sharp interest in the production of a single commodity. Everything that interfered with the efficient production of the key commodity was implacably eliminated. Everything that seemed unrelated to efficient production was ignored. Having come to see the forest as a commodity, scientific forestry set about refashioning it as a commodity machine. Utilitarian simplification in the forest was an effective way of maximizing wood production in the short and intermediate term. Ultimately, however, its emphasis on yield and paper profits, its relatively short time horizon, and , above all, the vast array of consequences it had resoloutley bracketed came back to haunt it.

Department of unintended consequences

I like to joke about wanting to start a department of unintended consequences to oversee economic policy. Often central planners fail because they arrograntly fail to foresee unintended consequences of their policies.

“ the door and window tax established in France under the directory and abolished only in 1917 is a striking case in point. Its originator must have reasoned that the number of windows and doors in a dwelling was proportional to the dwelling a size. Thus a tax assessor need not enter the house or measure it but merely count the doors and windows. As a simple, workable formula, it was a brilliant stroke, but it was not without consequences. Peasant dwellings were subsequently designed or renovated with the formula in mind so as to have as few openings as possible. While the fiscal losses could be recouped by raising the tax per opening, the long-term effects on the health of the rural population lasted for more than a century. “

See also: Goodhart’s Law

Biology and risk taking

Cleaning more book notes out of my Google Drive files…

Hour Between Dog and Wolf is a useful complement to Misbehaving and Thinking Fast and Slow. The author started out as a derivatives trader, then changed their career to neuroscience bringing unique personal perspective to the well worn path of studying how humans can act irrationality in financial markets and life.

Thinking Fast and Slow is a somewhat pendantic and rambling summary of groundbreaking research. Misbehaving is a humorous summary of the development of behavioral economics. Hour Between Dog and Wolf is a more personal story, with emphasis on dealing with risk and stress. All three are worth reading.

Written on the temple of Delphi was the maxim “know thyself” and today that increasingly knowing your biochemistry.

Brain-Body Connection

Probably the most valuable part of the book is a discussion of mind-body connection in the context of dealing with risk.

Category divide between body and mind, runs deep in western philosophy. This idea:

originated with Pythagoras, who needed the idea of immortal soul for his doctrine of reincarnation, but the idea of a mind-body split awas cast in its most durable form by Plato, who claimed that within our decaying flesh there flickers a spark of divinity, being an eternal and rational soul. The idea was subsequently taken up by St. Paul and enthroned as Christian dogma. It was a very edict also enthroned as a philosophical conundrum later known as the mind-body problem; and physicists such as Rene Descartes, a devout Catholic and committed scientist, wrestled with the problem of how this disembodied mind could interact with the physical body, eventually coming up with the memorable image of a ghost in a machine, watching and giving orders.

Today Platonic dualism as the doctrine is called is widely disputed within philosophy and mostly ignored in neuroscience, but there is one unlikely place where a vision of the rational mind and pure as anything contemplated by Plato or Descartes still lingers- and that is in economics.

Author argues that this platonic dualism has impaired ability to understand financial markets. Need to study how people react to volatile markets. For too long people have ignored brain body feedback.

Book goes on to discuss crazy behavior of traders, bankers, and the idiotic decision they made. Not original, but well worth reading, and the author puts a unique spin on it.

A couple other related ideas:

- Neocortex gave us reading, writing philosophy. Making tools throwing spears etc.

- Another brain region outgrew neocortex- cerebellum like a separate brain acting as operating system for rest of brain.

We may be gifted with considerable rational powers, but to solve a problem with them we must first be able to narrow down the potentially limitless amount of information, options and consequences. We face a tricky problem of limiting our search and to solve it we rely on emotions and gut feelings.

See also- Cialdini’s Law of Data Smog.

“Somatic Market Hypothesis”

Each event we store in memory comes bookmarked with the bodily sensations…. Called somatic markets we felt at time of living through it at our first time, and these help us decide what to do when we find ourselves in similar situations. These bookmarkers basically help us sort through options. Somatic markers help rational brain function.

Moving towards stress adaptation

Some scientists study stress and response too it. Chronic stress leads to illness, learned helplessness. Short lived bursts of stress, in contrast, cause people to emerge hardier. Can be verified with lab rats. Well known for anyone building muscle mass or aerobic capacity.

Humans are built to move, so we should. The more research emerges on physical exercise, the more we find that its benefits extend far beyond our muscles and cardiovascular systems. Exercise expands the productive capacity of our amine-producing cells, helping to inoculate us against anxiety, stress, depression and learned helplessness.It also floods our brains with what are called growth factors, and these keep existing neurons young and new neurons growing – some scientists call these growth factor brain fertilizer- so our brains are strengthened against stress and aging. A well -designed regime of physical exercise can be a boot camp for the brain.

Fatigue and focus

I once had a coach who told me “rest is a part of training. ” Similarly, one of the top performing hedge fund managers I know sleeps 9 hours a night, and is obsessed with importance of rest.

A recently developed model in neurosciences provides an alternative explanation of fatigue. According to this model, fatigue should be understood as a signal our body and brain use to inform us that than expected return from our current activity has dropped below its metabolic cost. The brain quietly searches for the optimal allocation of attentional and metabolic resources and fatigue is one way it communicates its results. If we are engaged in some form of search and have not turned up any results, our brain, through the languages o fatigue and distractibility tells us we are wasting our time and encourages us to look elsewhere. The cure for fatigues, according to this account, is not rest, it is a fresh task. Support form this idea comes from data showing that overtime work in itself does not in itself lead to work-related illness such as hypertension and heart disease, these occur mainly if workers have no control over allocation of their attention. Applying such a model could benefit workers and management alike, for more flexibility in choosing what to work on, and when, could reduce worker fatigues, while management might be delighted to find that workers may be just as refreshed by a new assignment as by a vacation. This model of fatigue provides a good example of how understanding a bodily signal can alter the way we deal with it.

Only complaint about Hour Between Dog and Wolf is it probably could have been a long form article- I suspect the book publisher wanted to fill it out. Still worth taking a look though. Hour Between Dog and Wolf provides a useful framework for anyone who has a high stakes job that requires stamina.

See also:

Askeladden Capital on Sleep/Rest/Chronotypes Mental Model

Askeladden Capital’s review of Misbehaving

Optimizing An Organized Mind

How can one maximize mental performance? The Organized Mind- Thinking Straight in an Age of Information Overload by Daniel Levitin is a book that works towards an answer to this question. The book’s ideas on offloading things to external systems and organizational techniques are very similar to David Allen’s , Getting Things Done . However, The Organized Mind, provides much more historical and scientific background an context. Further, An Organized Mind avoids being overly prescriptive, and instead gives the reader ideas on how to best optimize for their own situation.

Some of my highlights on the key themes of the book:

Getting the mind into the right mode

One useful framework that the books develops is hte idea of the mind as functioning in different modes. An important component of high performance is the ability to use the right mode at the right time.

There are four components in the human attention system: the mind-wandering mode, the central executive mode, the attention filter, and the attention switch, which directs neural and metabolic resources among the mind-wandering, stay-on-task, or vigilance modes.

…

Remember that the mind-wandering mode and the central executive work in opposition and are mutually exclusive states; they’re like the little devil and angel standing on opposite shoulders, each trying to tempt you. While you’re working on one project, the mind-wandering devil starts thinking of all the other things going on in your life and tries to distract you. Such is the power of this task-negative network that those thoughts will churn around in your brain until you deal with them somehow. Writing them down gets them out of your head, clearing your brain of the clutter that is interfering with being able to focus on what you want to focus on. As Allen notes, “Your mind will remind you of all kinds of things when you can do.

…

The task-negative or mind-wandering mode is responsible for generating much useful information, but so much of it comes at the wrong time.

…

Creativity involves the skillful integration of this time-stopping daydreaming mode and the time-monitoring central executive mode.

Insights into how human memory works

The book delineates the nuances of human memory by comparing it to systems in the physical world.

Being able to access any memory regardless of where it is stored is what computer scientists call random access. DVDs and hard drives work this way; videotapes do not. You can jump to any spot in a movie on a DVD or hard drive by “pointing” at it. But to get to a particular point in a videotape, you need to go through every previous point first (sequential access). Our ability to randomly access our memory from multiple cues is especially powerful. Computer scientists call it relational memory. You may have heard of relational databases— that’s effectively what human memory is.

Having relational memory means that if I want to get you to think of a fire truck, I can induce the memory in many different ways. I might make the sound of a siren, or give you a verbal description (“ a large red truck with ladders on the side that typically responds to a certain kind of emergency”).

This feature can lead to either valuable insights or being overwhelmed, depending on how it is controlled:

If you are trying to retrieve a particular memory, the flood of activations can cause competition among different nodes, leaving you with a traffic jam of neural nodes trying to get through to consciousness, and you end up with nothing.

Categorization is key to mental functioning.

This ability to recognize diversity and organize it into categories is a biological reality that is absolutely essential to the organized human mind.”

Shift burdens to external systems

You might say categorizing and externalizing our memory enables us to balance the yin of our wandering thoughts with the yang of our focused execution.

9 Steps to 10x Thinking

Smartcuts: How Hackers, Innovators, and Icons Accelerate Success is a book about the power of lateral thinking- solving problems through an indirect or creative approach. “Smartcuts” means sustainable success achieved through smart work. This is different than “shortcuts”, which are rapid, but short term gains. Ultimately the book outlines 9 key ideas, that lead up to the concept of “10x thinking”.

#1 Hacking the Ladder

Find sideways paths, like the warp pipes in Super Mario that allows someone to beat the game in seconds, not hours.

#2 Train with Masters

Find mentors, and/or study the greats. Shoe designer Dwayne Edwards stole discarded shoes so he could study and draw the designs. This helped him develop the ability to notice tiny design details in shoes.

#3 Rapid Feedback

Rapid feedback accelerates learning. This has been critical to a lot of companies that have a website as their main product. In this book, the example of Upworthy illustrates the point. Turn work into rapid scientific experiments, and depersonalized feedback.

#4 Platforms

Tools and technology that people can buid off of. a platform “amplifies the effort and teaches skills in the process of using it.“ Key example: development of Ruby on Rails as a programming language.

Platforms are how Twitter could build Twitter in mere days while running a separate company. And Platforms are why Finland made all its teachers get a Master’s degrees and its students learn with hands-on tools that made learning better.

See also: Modern Monopolies: What It Takes to Dominate the 21st Century Economy

#5 Catching waves

The world’s best surfers arrive at the beach hours before a competition and stare at the ocean. This is a valuable metaphor for a lot of things in business and life.

“Intuition is the result of nonconscious pattern recognition,” ….. However, research shows, that we can also see patterns just as well by deliberately looking for them. Deliberate pattern spotting can compensate for experience. “but often people don’t even try it”

Budgeted Experimentation helps business avoid being disrupted, by helping them harness waves on which younger competitors might otherwise used to ride past them. Its helped companies like Google, 3M, Flickr, Conde Nast, and NPR remain innovative even as peer companies plateaued. In contrast, companies that are too focused on defending their current business practice and to fearful to experiment often get overtaken.

Key example of what to avoid: Kodak

#6 Superconnecting

Key example: Che Guevera taking control of the radio, using it as a way of promoting Castro’s revolution to a much wider audience than otherwise possible.

#7 Momentum

Build up potential energy, and amplify unexpected opportunities.

#8 Simplicity

The key feature of disruptively innovative products is cost savings(either time or money). But the key ingredient behind the scenes of every disruptive product is simplification.

Examples, email, USB Drives, Cars.(Henry Ford kept complexity under the hood).

Key example: Sherlock Holmes. He focused on what he needed to know, knowing how to figure out what he didn’t know, and forgetting about everything else.

#9 10x thinking

This quote from Astro Teller is key:

Its often easier to make something 10 times better than it is to make it 10 percent better…. In order to get really big improvements you usually have to start over in one or more ways. You have to break some of the basic assumptions and, of course, you can’t know ahead of time. Its by definition counter intuitive.

This means getting to first principles. 10x thinking forces you to come up with smartcuts.

10x thinking is probably now essential for survival in the modern economy.

Most innovation inside industries and companies today focuses on making faster horses, not automobiles.

This is why the innovator’s dilemma destroy’s so many companies. What replaces them is something better. Creative destruction is a beautiful thing.

Disrupting Through Good Customer Service

In Zero to One Peter Thiel theorizes that a new innovation must be at least ten times better than the currently existing solution in an important dimension. This is a high bar, but it often achieved by focusing on an ignored or under exploited niche.

The examples of Uber, and Amazon show how focusing relentlessly on customers can also achieve this goal, especially when incumbents are attached to an old way of doing things that is unpleasant for customers. Good customer service can be extremely disruptive.

When facing regulatory challenges, Uber’s CEO Travis Kalanick went against conventional wisdom of his lobbyists. Rather than seeking to compromise with regulators, he focused on delivering a better product. In The Upstarts the author discusses what is known as “Travis’ law:

“Our product is so superior to the status quo that if we give people the opportunity to see it or try it, in any place in the world where government has to be at least somewhat responsive to the people, they will demand it and defend its right to exist.”

Mobilizing customers is Uber’s public affairs strategy.

This extreme focus on customers was a key factor in Amazon’s rise as well. Here is Jeff Bezos in the early days of Amazon(quoted from The Everything Store):

“You should wake up worried, terrified every morning. But don’t be worried about our competitors because they’re never going to send us any money anyway. Lets worried about our customers and stay heads down, focused.”

Bezos reiterated this sentiment in the most recent annual letter:

There are many ways to center a business. You can be competitor focused, you can be product focused, you can be technology focused, you can be business model focused, and there are more. But in my view, obsessive customer focus is by far the most protective of Day 1 vitality.

Why? There are many advantages to a customer-centric approach, but here’s the big one: customers are always beautifully, wonderfully dissatisfied, even when they report being happy and business is great. Even when they don’t yet know it, customers want something better, and your desire to delight customers will drive you to invent on their behalf. No customer ever asked Amazon to create the Prime membership program, but it sure turns out they wanted it, and I could give you many such examples.

I can’t help but wonder if financial services will end up facing a similar level of disruption from Robo Advisers. Most of the financial services industry is clearly conflicted and not focused on actually improving client outcomes. That leaves a massive space for new entrants.